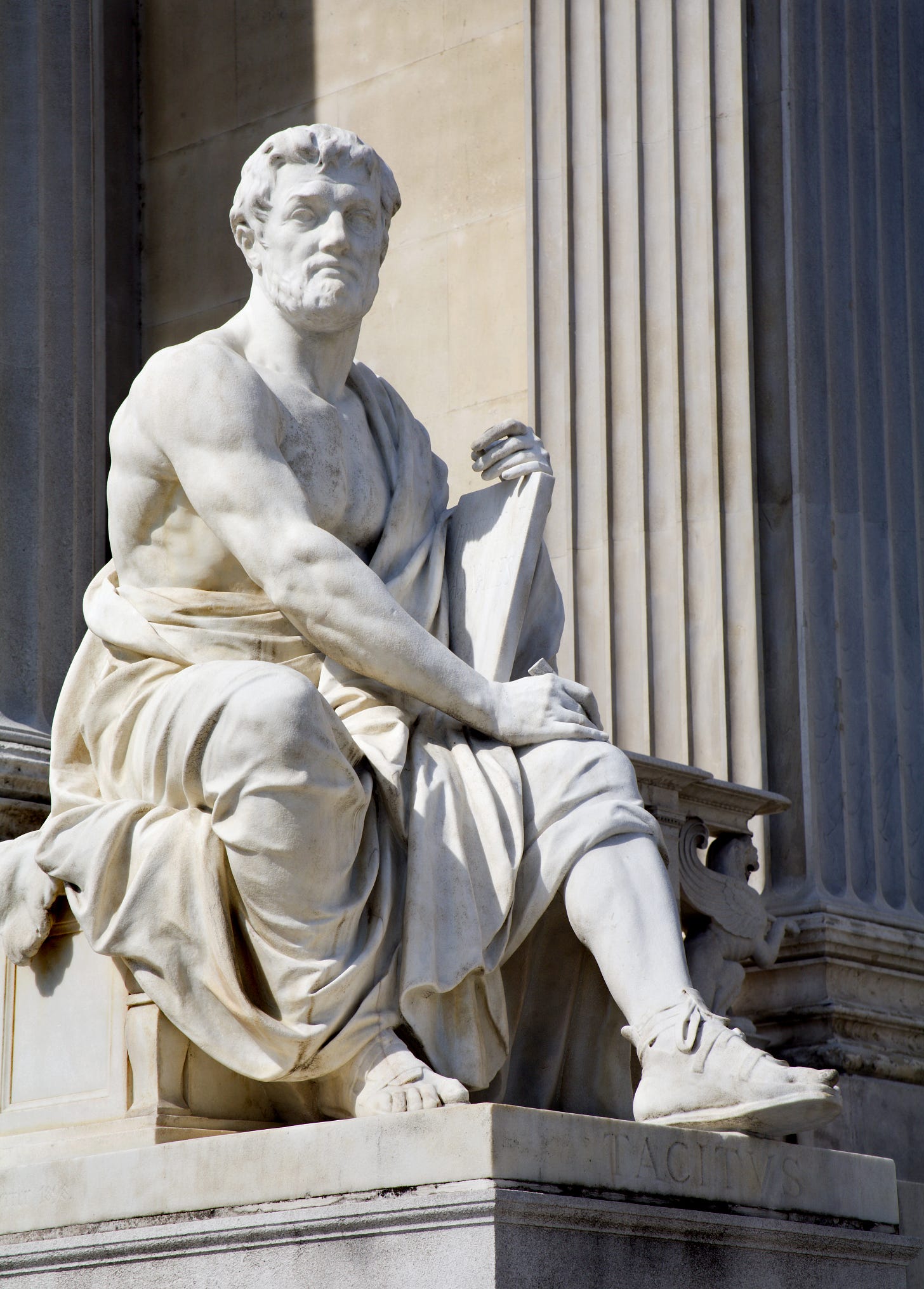

Sidekicks—from Dr. Watson to Tacitus

Why mystery writers keep creating them

I’ve just finished The Blood of Caesar, the second book in Albert Bell, Jr.’s Roman Empire mystery series. Bell’s amateur detective is Pliny the Younger, a historical figure who wrote letters describing nearly every aspect of Roman life (The collection is available on Spotify).

This mystery begins when the emperor Domitian asks Pliny to inspect a corpse found in the palace library. Is it a murder or not? As the investigation unfolds, Bell weaves in fascinating detail about Rome’s imperial families and its villas, monuments, and public baths. The book is fast-paced and entertaining, but Bell, to his credit, doesn’t gloss over Rome’s unthinking acceptance of slavery and rampant corruption. He reveals and examines them.

In Bell’s hands, Pliny is quick-witted and resourceful, someone pursuing truth in a deceitful world. And like many fictional detectives, he has a sidekick, the Roman historian, Tacitus. Both are young, at the beginning of their careers. Pliny sums up their crime-solving partnership: “One of us sometimes sees what the other misses.”

Not all imaginary detectives have sidekicks—Miss Marple and Columbo don’t. But many iconic sleuths have associates who appear in story after story: Sherlock has Dr. Watson. Inspector Morse has Sergeant Lewis. The web site, Crime Reads, ranks “45 of the greatest detective-adjacent crime-solvers in history.” They omitted a few of my favorites, but it’s a fun listicle.

Historical sidekicks

Earlier this year, I reviewed three superb historical mystery series and posted about a fourth, Albert Bell’s Pliny books. And wouldn’t you know? All four series detectives have sidekicks. Below, I’ll suggest why writers so often include this supporting role. First, here’s a quick guide to my examples:

Albert A. Bell Jr.’s Notebooks of Pliny the Younger—8 Books.

Detective: Pliny the Younger

Sidekick: Tacitus

Andrew Taylor’s Marwood and Lovett English Restoration mysteries—6 Books.

Detective: James Marwood, a royal clerk and occasional government spy.

Sidekick: Cat Lovett, an heiress who’s been cheated out of her inheritance.

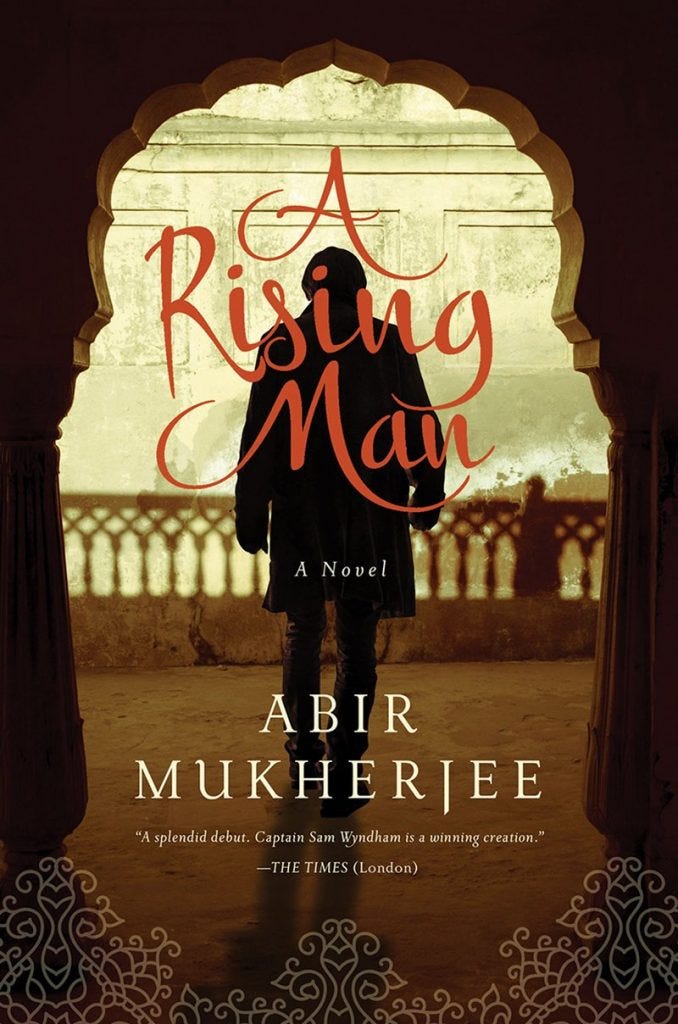

Abir Mukherjee’s British Raj police procedurals—5 Books.

Detective: Captain Sam Wyndham, an English police detective working in Calcutta.

Sidekick: Police Sergeant Surendranath Banerjee—called “Surrender-not” by British colleagues who smirk at his name.

C.J. Sansom’s Tudor mysteries—7 Books and a TV Mini Series

Detective: Mathew Shardlake, a lawyer whose clients range from Thomas Cromwell to Katherine Parr.

Sidekick: Jack Barack, a one-time Cromwell “rogue.”

So what’s up with the sidekicks?

Aspiring mystery writers can find plenty of advice on why “your detective” needs a sidekick and how to invent an interesting one. The Mystery & Suspense web site suggests that “sidekicks are the heart of mystery fiction . . . a counterbalance to the often solitary and obsessive nature of detectives.” Based on my reading and viewing, they can be verbal sparring partners, tech help, comic relief, or love interest. From the writer’s point of view, including a sidekick can improve your story in several ways:

They serve as a foil to the lead detective.

Often, the sidekick’s age, gender, personality, and abilities are an intentional contrast with the detective. In Bell’s Roman mysteries, Pliny is earnest, romantic, and unlucky in love. Tacitus is joyfully promiscuous. Sansom’s Tudor lawyer, Mathew Shardlake, is honorable, intelligent, and physically disabled—he’s sometimes mocked as a “hunchback” on the street. Sidekick Jack Barack is younger, cheekier, handy with a sword, and quick to leap into a fight. In both series, the authors emphasize the lead characters’ contrasting dispositions to inject more drama into their adventures.

They introduce missing perspectives.

Nearly all mysteries have the same plot: The detective looks for a murderer and eventually succeeds. The protagonist’s journey shapes the narrative. But sidekicks can bring in distinctive outlooks and life stories that make a book more compelling.

In the Taylor’s Marlett and Lovett Restoration series, the two aren’t professional associates, although they repeatedly find themselves ensnared in the same mysteries. Cat’s story adds depth by illustrating the treatment of women in seventeenth century England. She is raped by her cousin, but can do nothing about it. She aspires to be an architect in an era when women of her class are expected to give birth and host dinner parties.

In a similar vein, Abir Mukherjee’s Sergeant Surendranath Banerjee is named after a historical nationalist leader. Captain Wyndham is a reasonably fair-minded Englishman, but he’s an observer of India’s plight. Banerjee is the one who embodies his country’s long battle against racism and exploitation. When an investigation brings Wyndham and Banerjee to The Bengal Club, they encounter a sign, “No dogs or Indians beyond this point.” The sergeant has to wait outside.

The sidekick’s interaction with the lead can be a subplot.

I’m just beginning the Pliny and British Raj series, so I don’t know what’s to come for the investigating duos. How fabulous to have more books to go! But I’m halfway through Taylor’s Restoration series, and Marwood and Lovett seem to be falling in love. So far, they’ve viewed each other with suspicion. Sometimes their interests conflict. But I sense a growing affection between them, and being a committed romantic, I’m crossing my fingers for them.

In Samsom’s Tudor mysteries, Shardlake and Barack are initially wary of each other. They live in an environment when any new acquaintance could be a spy. The term, “eavesdrop” (as we use it) spread in the sixteenth century when servants and attendants often positioned themselves to overhear and report on their patrons. Shardlake and Barack become friends over time, but then stuff happens. Sansom was apparently planning an eighth mystery before his death in April 2024, but fans shouldn’t worry. His last book, Tombland, ends with Shardlake and Barack in a satisfying place.

Beyond mysteries

Sidekicks aren’t limited to detective stories. Western sheriffs sometimes have them. “Buddy” movies are a thing. Maybe the pervasiveness of this role reflects a fundamental human desire. Most of us have special friends we rely on. Few of us can get by alone.

The Queen’s Musician, my forthcoming novel, tells the story of Mark Smeaton, a largely unknown historical figure. He was “lowborn,” as they liked to say at the time, but became one of Henry VIII’s favorite musicians. His talent brought him comfort and prosperity, but he was isolated among ambitious, privileged people. In my novel, he regularly confides in fellow player—he has a sidekick, if you will. Their conversations in moments of success and danger allow me to reveal more about my young protagonist. I hope Mark Smeaton had such a friend.

How could I leave this topic without Lennon and McCartney’s “I get by with a little help from my friends.” You can listen to the classic Ringo version or the incomparable Joe Cocker.

Let me know if you have your own favorite fictional detective and sidekick. Who are they? What makes them an intriguing pair?

Can I supplement with another reason for sidekicks. A mystery often turns on the detective putting together clues rather than physically doing something, as in a police procedural. Since some of the crucial steps happen inside the detective's mind, we readers have no direct access to the crucial events. A sidekick gives the detective someone to explain the deduction too. This is the role of Dr. Watson -- Sherlock Holmes explains his thought processes to Watson. So, my theory is, the sidekick serves as a way for us to access the detective's internal thought process.

For some reason Jane Austen popped to mind. Her heroines usually have a sister or friend who plays the role of a sidekick as you've defined.