Fictional Detectives Through the Ages

My favorite mystery series from C. J. Sansom, Andrew Taylor, and Abir Mukherjee

I recently asked my helpful bot to identify the world’s first detective. It suggested Eugène-François Vidocq, a one-time thief who joined the Paris police and organized its first plainclothes detective unit in 1812. Some believe Vidocq was the historical model for Edgar Allen Poe’s Auguste Dupin. Poe published three Dupin stories, starting with “The Murders in the Rue Morgue" in 1841.

I was happy to learn about Vidocq, but I had assumed that “detectives” had existed for millennia. Crime investigation may not be the world’s oldest profession, but societies must have needed people to hunt down murderers since the dawn of civilization. After all, Oedipus Rex begins as a search for the man who killed Jocasta’s first husband. The fateful complications proceed from there.

Perhaps my bot is a literal thinker and considered only professional detectives working in police departments.

Historical novelists are more imaginative. They’ve conjured up “detectives” in eras across the ages. Umberto Eco’s The Name of the Rose features a fourteenth century monk who investigates suspicious deaths in a mysterious Italian abbey. Ellis Peters’ hugely popular Cadfael series introduces another crime-solving monk, this one in twelfth century England. The sublime Derek Jacobi played the role in the PBS anthology, Mystery!

Goodreads offers a long list of mysteries set in Ancient Rome. I’m just delving into it—more on that to come. Meanwhile, here are three historical detective series I’ve enjoyed.

Tudor England: C. J. Sansom’s Matthew Shardlake mysteries take place during the reigns of Henry VIII and Edward VI. This author crafts his intricate mysteries in the context of social and economic upheavals such as the dissolution of the monasteries and the enclosures of common land. Shardlake is a lawyer—a humane, conscientious, and lonely man. I’ve read six of the seven mysteries and become quite fond of him.

So far, Lamentation is my favorite: Katherine Parr is queen to an aging Henry VIII in an era of religious turmoil and fanaticism.

A few pages in, a minor character describes the looming execution of four heretics: “The burning is to be a great spectacle. There has been nothing like it for years. The King wants it to be seen where heresy leads. Half the Privy Council will be there.”

In real life, the reformist Katherine wrote about her faith in a text called “The Lamentation of the Sinner.” The document wasn’t published until after Henry’s death, but some at court knew of it and claimed it was heretical.

In Sansom’s novel (though not in real life), the queen’s enemies have stolen the manuscript with plans to disseminate it broadly—an act that would enrage the king and doom the queen. She calls on Matthew Shardlake to retrieve it before it can be printed.

If you remember the student mnemonic about Henry’s six wives—“Divorced, beheaded, died; divorced, beheaded, survived”—you know that Katherine Parr outlived her mercurial husband. She didn’t publish The Lamentation until she knew the coast was clear. Regular readers of Historical Magic might recall that my own forthcoming novel (May 2025) is also set in Henry’s reign. It’s not a detective mystery, but it is about a man accused of crimes that carry a sentence of death.

Restoration England: The Ashes of London is the first novel in Andrew Taylor’s Marwood and Lovett mysteries.

In the opening, a young clerk named James Marwood watches the collapse of the old St. Paul’s cathedral during the 1666 Great Fire. “The noise was the worst. Not the crackling of the flames and clatter of falling buildings . . . it was the howling of the fire . . . It was the voice of the Great Beast itself. Part of the nave fell in.” Much of this book’s power lies in its graphic depiction of the devastated city and its shocked inhabitants. Sir Christopher Wren makes an appearance.

Marwood soon encounters Cat Lovett, a young woman who dreams of becoming an architect. Both appear in the subsequent novels, and despite romantic sparks between them, they bicker and mystify one another. I’ve read four of the six books available, and personally, I find Cat too hot-headed and impulsive. But perhaps her behavior is understandable. She has to endure the injustice and indignity women faced at the time. Early on, she is forced into a marriage to a much older man. Taylor’s rendering of her inevitable surrender to society’s rules is both subtle and indelible.

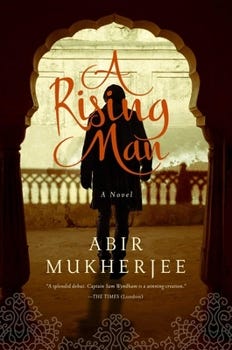

The British Raj: I’ve just finished the first of Abir Mukherjee’s Captain Wyndham and Banerjee police procedurals (There are currently five). A Rising Man, set in 1919 Calcutta, is twisty and absorbing, with a vivid cast of characters.

Captain Wyndham is a haunted, opium-addicted British detective; Banerjee is his likeable and very efficient Brahmin sergeant. Their first case concerns an Indian freedom fighter about to be hanged for murdering a prominent British official. When Wyndham and Banerjee realize he’s not guilty, they hunt for the real killer despite opposition from their colleagues. Captain Wyndham narrates, mixing storytelling with biting asides on the colonial mentality. He describes one government building: “[There were] huge columns topped off with statues of the gods. Not Indian gods of course. These ones were Greek or possibly Roman . . . It was the architecture of domination.”

Mukherjee has a gift for weaving the smug, racist mindset of the British Raj into the novel without making it a history lesson or sanctimonious rant. For me, this author is a major find—I’ve added his other books to my list.

As someone who enjoys mysteries almost as much as historical fiction, I find the combo tempting. Most mysteries have an unbeatable “hook”—there’s a murder, and no one knows who did it. Add some wily investigators and a well-done historical backdrop, and the result can be irresistible.

So interesting. I really want to follow up on some of the books you mentioned. Thanks for this fabulous blog. I look forward to every issue.

Jean, this is terrific. As always. So well written, so engaging, so damn interesting.