Looking for a Novel about Pliny the Younger?

I wasn’t either, but now I’m hooked: Albert A. Bell, Jr.’s Roman Empire detective mysteries

Several posts ago, I recommended some of my favorite historical detective series, books set between the Middle Ages and early twentieth century. At the time, I promised to look into mysteries taking place in the ancient world, and quite joyously, I’ve found what promises to be an addictive series. Pliny the Younger is the investigator, aided by his trusty friend, Tacitus.

History professor Albert A. Bell, Jr. has published eight Pliny novels so far, and I started with the first: All Roads Lead to Murder. In an afterword, Bell explains that he admired and wrote scholarly articles about Pliny long before casting him as a fictional detective. Truth be told, I was hazy on Pliny. I knew he was Roman—I would have aced a multiple choice exam if the other choices suggested he was Egyptian or Greek. I was confident he wasn’t an emperor. Beyond that, I would have been guessing.

Just to bring everyone up to speed, Encyclopedia Britannica describes Pliny the Younger as an “author and administrator” [known for his] collection of private letters that intimately illustrated public and private life in the heyday of the Roman Empire.” Centuries later, you can listen to his letters on Spotify.

His father died when he was a boy, and he was adopted by his uncle, Pliny the Elder. The older Pliny wrote works on astronomy, botany, and medicine and commanded the Roman fleet in the Bay of Naples. Both uncle and nephew witnessed in the eruption of Vesuvius, and the elder Pliny died trying to rescue friends.

All Roads Lead to Murder is a traditional mystery that offers fast-paced entertainment and absorbing detail about Roman life. Bell is not a literary stylist, nor is his plot one of those bone-chilling, “smack-your-forehead” shockers. Yet once I began reading the novel, I was eager to get back to it every chance I had. Bell mixes classic whodunit elements with an utterly appealing “detective” and a vivid depiction of the past.

The mystery:

The murder. It’s quite grisly, but there’s not much blood. Naturally Pliny wonders about this.

The setting. No English country house, but there is an inn in Smyrna. The plot rolls out in this Greek trading city on the Aegean Sea. Smyrna is now called Izmir.

The suspects. A caravan of travelers journeying from Antioch to Rome. They spend a night at the inn, and the next morning, a disagreeable Roman is dead with his heart cut out. The traveling group includes Greeks, Germans, Jews, early Christians, and of course, wealthy Romans, many with a reason to dislike the victim.

The detective. Here, Pliny is in his early twenties. He’s one of the travelers and lacks any clear authority to investigate. He’s conscientious and curious but often makes mistakes and regrets them. For me, this mix of shrewdness and floundering makes him more appealing than inscrutable geniuses like Sherlock and Poirot. His youth is also an asset. At one point, he asks himself, “What [am] I going to do with my life? [Will] I ever accomplish as much as my uncle did?”

The sidekick. While I was reading, I wondered whether Pliny’s friend, Tacitus, was the Tacitus. The afterword assured me he is. Here, Tacitus is young, dashing, and completely promiscuous. He’s also loyal and brave.

Red herrings. The author misled me at key points, but the pleasure in reading this mystery is in the characters and setting, not a stunning reveal at the end.

Bell’s Smyrna is a dusty, provincial town with an agora, Roman baths, a temple dedicated to Artemis, and an old quarter of hidden lairs and filthy streets. The author incorporates the empire’s diverse religions into the plot. There are Roman rites, secret Christian gatherings, and pagan rituals, along with a witch’s curse. In his afterword, Bell explains that the real life Pliny was “a thoroughgoing skeptic when it comes to religion and the afterlife.” This is the Pliny we meet in the book. I won’t tell you how, but the fictional Pliny receives a copy of an early Christian gospel. He’s too preoccupied with the murder investigation to read it.

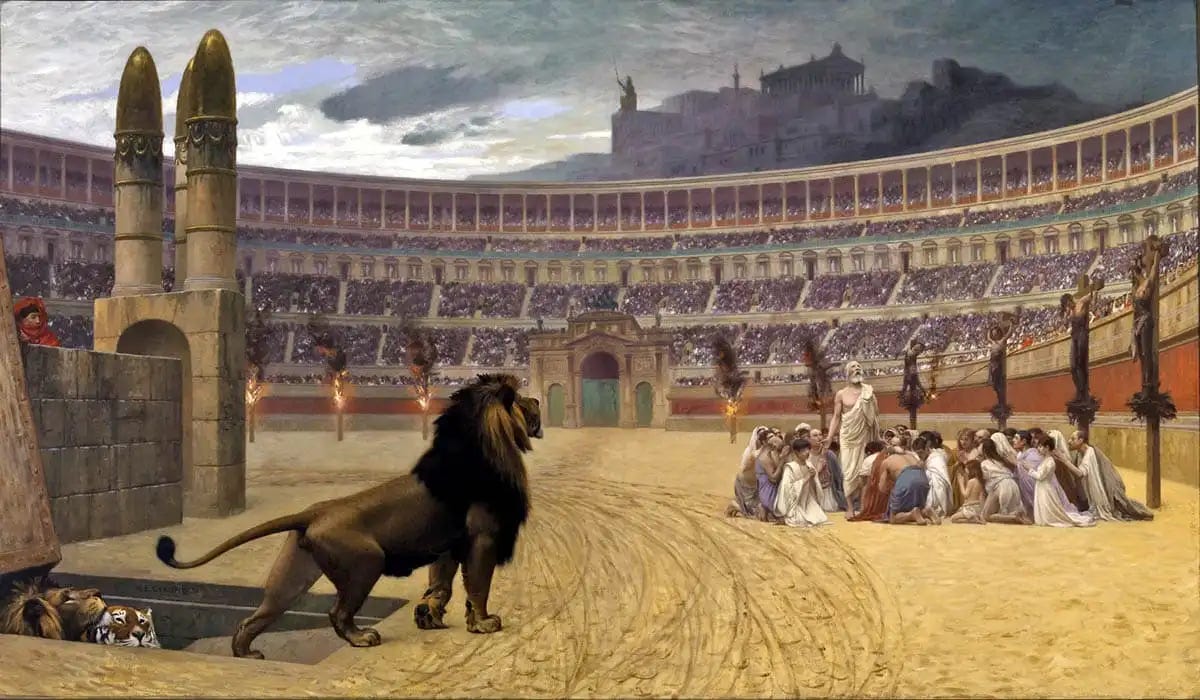

When I start a historical novel, I often wonder what I’ll learn. In this case, Professor Bell has crafted a fun-to-read mystery, but one with a definite point of view: School teachers may point to the splendid architecture, engineering, and oratory, but beneath its luster, the Roman Empire was a very nasty place.

Callousness to human suffering

In the novel, a powerful man organizes “games” for the populace—ferocious animals let loose on defenseless humans, petty criminals crucified. Slaves are casually used, abused, and branded. Bell leaves the details to the readers’ imagination, but I occasionally asked myself whether the book was too lurid. Yet Roman barbarism was a reality. It would be misleading to airbrush it.

Injustice and tyranny

According to Bell, Pliny’s letters reveal a “humane, generous man who feels confined by an increasingly dictatorial regime.” The fictional Pliny fights against a justice system that accepts confessions obtained through torture while ignoring physical evidence. He complains about a rising class of Romans who are “dissolute, dissipated, interested in nothing but their own advancement.”

Slavery

Pliny and Tacitus are men of their time, and they accept slavery as a given. Bell doesn’t sugarcoat this fact. But the author also underscores the depravity of one human being owning another—or of wealthy Romans owning dozens of people. In the novel, the local authorities plan to torture every slave in the murdered man’s household, regarding this as an efficient form of “questioning.” Pliny takes significant risks to try to stop this horror. He may not see the core immorality of slavery, but he is drawn to protect the powerless.

A few readers may breeze through All Roads Lead to Murder giving little thought to the Roman Empire’s grim underbelly. I suspect most will be unsettled by the stark inequality and outright cruelty. Roman citizens had significant rights and privileges. Others could be brutalized until death—all under the law.

Today, we’re not as heartless as the Romans—I can say that without hesitation. Humanity has inched forward in many respects. But when I read the news, both from the U.S. and abroad, I sometimes ask myself how much better we are. We may not like to watch human suffering, but we often ignore and tolerate it.

Terrific, as always. I knew about as much about Pliny as you wrote - Roman, man of distinction. Period. The novel sounds fascinating. Thanks for sharing.

Thanks for the like, Gabi.

And Margaret, thanks for your good question and insights. To answer directly, I was actually thinking about humanity in general when I wrote that sentence, i.e., that slavery and human torture as entertainment are no longer openly accepted as they were during the Roman Empire. To your point, we still turn our eyes away from countless forms of cruelty and human suffering. For example, human trafficking and forced labor are more likely to be hidden now. My guess is that most people in most places would say that these are horrible practices that should be stopped., Yet they persist, as do many other cruelties--war crimes, terrorism, mass starvation. So has humanity progressed or not? Maybe we're just more hypocritical. But I do remember Dan Yankelovich saying that what people give lip service to is important. He considered it a first step toward change. I wish we could talk to him about what's happening now.