Next week, PBS launches a new installment of Wolf Hall. We’re back to Henry VIII, Thomas Cromwell, serial queens, gorgeous palaces, and outstanding hats. I’ll be watching for sure.

When I began writing my own Tudor novel (out in May), I noticed that people tend to have a favorite among Henry’s six queens. Katherine of Aragon, Anne Boleyn, and Katherine Parr generally top the list, although Anne of Cleves and Jane Seymour have their fans. But I’ve yet to encounter anyone who picks Katheryn Howard. She was Henry’s fifth wife, the second to be executed for adultery. Her fate is shocking, but her actions seem incomprehensible.

By today’s standards, her circumstances were deeply unfair. The nineteen-year-old had little choice about marrying the forty-nine-year old monarch—you don’t refuse the king. And she knew the risks for queens suspected of infidelity. Her cousin Anne Boleyn had been executed four years earlier.

Yet Katheryn appointed a former lover (Francis Dereham) as her secretary and met secretly with one of Henry’s grooms (Thomas Culpeper). Tudor historian Claire Ridgway has an entertaining YouTube video posing the one question she’d like to ask each wife. Ridgway’s question for Katheryn is the same as mine: “What were you thinking?”

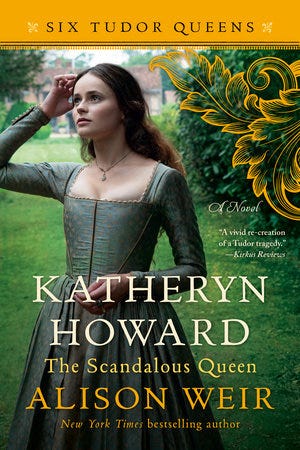

So here’s a situation ripe for historical fiction. We have some key facts—the queen and others were charged and executed. Yet much is unknown or in dispute. Nearly five hundred years later, no one is sure why this young woman did what she did. Alison Weir suggests some reasons in her absorbing, but troubling novel about Henry’s fifth wife: Katheryn Howard: The Scandalous Queen.

Alison Weir is a prolific Tudor historian. I consulted her nonfiction bio of Anne Boleyn, The Lady in the Tower, while working on my novel, The Queen’s Musician. But Weir also has an ability to weave dry, disjointed documentation into an absorbing, digestible story. She’s written novels on all of Henry’s wives, plus Mary I and Cardinal Wolsey.

Here's what interested me when I opened Weir’s novel and what remained with me after I finished.

What did Katheryn Howard do?

Weir accepts the prevailing historical judgment that most of the charges against Katheryn were true. The novel depicts her prior sexual relationship with Francis Dereham who claims they are “precontracted,” i.e., bound together as husband and wife. Katheryn loses interest in Dereham when she becomes a lady-in-waiting to Anne of Cleves. Once the king begins wooing Katheryn, she says she is a virgin. As queen, she luxuriates in her costly gowns and jewels. Over time, she starts meeting with Culpeper privately, sometimes late at night.

It’s worth noting that Katheryn Howard’s downfall is very different from Anne Boleyn’s. As Claire Ridgway explains in this excellent video, Anne and the five men executed as her lovers were almost certainly innocent. The crown concocted evidence against them so Henry could oust Anne quickly—he wanted to marry Jane Seymour, wife number three. But Henry doted on Katheryn up until the moment he found out about her deceptions. He was distraught when he learned the truth.

Why did she do it?

Like any good novelist—or lawyer—Weir suggests some mitigating factors for Katheryn’s behavior. She essentially grew up parentless. Her mother died when she was a child; her father was unreliable. At an impressionable age, she joined the household of the Dowager Duchess of Norfolk where she slept in a dormitory with young women who invited their beaus to visit and coupled with them openly. In a few years, Katheryn was canoodling with her music teacher.

In this fictional account, Weir shifts some of the blame to others. She paints Dereham as a blackmailer demanding a court position to remain silent about Katheryn’s past. She portrays Lady Rochford, one of Katheryn’s attendants, as urging and encouraging the assignations with Culpeper. In real life, Lady Rochford was executed as an accomplice, but some historians think she was only doing Katheryn’s bidding.

In the end, the reason behind Katheryn’s recklessness may be the most obvious: “the crazy things we do for love.” Let’s say you’re barely twenty and head-over-heels for an attractive young guy. You can’t be with him because you’ve been forced to marry an obese old geezer. From time immemorial, humans young and old have taken stupefying risks for romantic love. Look at Cleopatra.

Was the punishment unfair?

Weir emphasizes that for the Tudors, Katheryn’s crimes were more serious than infidelity. They threatened the succession and the throne. If she was “precontracted” to Dereham (as he maintained), the royal marriage would have been invalid; any children would have been illegitimate. If she was unfaithful during her marriage, any son might not be the king’s true son. They didn’t have DNA testing.

Pretenders were a genuine threat in this period. England was finally at peace after The War of the Roses, thirty years of fighting among families with varying hereditary claims to the throne. To Henry, doubts about his children’s parentage could have been the pretext for another civil war.

But Weir also dramatizes Tudor England’s appalling lack of justice. Katheryn didn’t know who had accused her or what they had said. She had no trial—the House of Lords voted her guilty through a bill of attainder. Good luck with that in an absolute monarchy. She wasn’t allowed to see Henry to ask for mercy. On February 13, 1542, she was beheaded.

It's tempting to view Katheryn through a modern lens—to see her as an abused young woman groomed by her family and used by powerful men. That’s partially true. But she also made decisions that led to her own downfall. Weir doesn’t take the “weren’t they all terrible” route.

Instead, she shows us two Katheryns. One is a beautiful, vivacious charmer who stole the king’s heart and liked being queen. The other is an emotionally immature young woman repeatedly drawn to handsome young admirers, some of whom she abandoned quite suddenly. Weir depicts her with empathy but doesn’t idealize her.

How would you explain Katheryn Howard’s behavior? And what do you think of Henry? Will you be watching Wolf Hall next week? Let us know what you think.

“Little is known about Mark Smeaton beyond his tragic fate. Yet Johnson imbues him with depth and dignity, transforming a historical footnote into a fully realized character whose story lingers long after the final page.”

PRE-ORDER NOW AT MAJOR BOOKSELLERS. AVAILABLE MAY 27, 2025.

Fascinating commentary! This is the most thorough and nuanced explanation of wife 5 I have ever read. Makes her into a real person and not a cartoon

I think Katherine could have been naively reckless and tempting fate as only a 19 year old would do.