Will People Read My Book If They Already Know the End?

Historical novels often tell familiar tales. Why would readers be interested?

During last week’s amazing events at the Vatican, I watched a TV interview with the author of Conclave, Robert Harris. Talk about having a timely book. As the segment opened, the interviewer assured Harris he wouldn’t reveal Conclave’s final plot twist. Don’t worry, the message was: If you plan to read this novel or see the film, I won’t ruin it for you.

It’s a thing—our informal compact to protect our chance to be surprised. And bombshell endings are popular. You can find a slew of online articles recommending books or movies that feature them. As a writer, I’m in awe of novelists whose plots veer off into unforeseen directions—Gillian Flynn’s Gone Girl, Jean Hanff Korelitz’s The Plot, and Colleen Hoover’s Verity come to mind.

My ending is common knowledge

But suppose your book doesn’t have a surprise ending? Historical novels often involve familiar people and events. If you pick up a novel about Julius Caesar or Marie Antoinette or Billy the Kid, you probably know the protagonist’s ultimate fate. The last chapters may be memorable or heartbreaking or petrifying, but you’re not likely to be caught off guard.

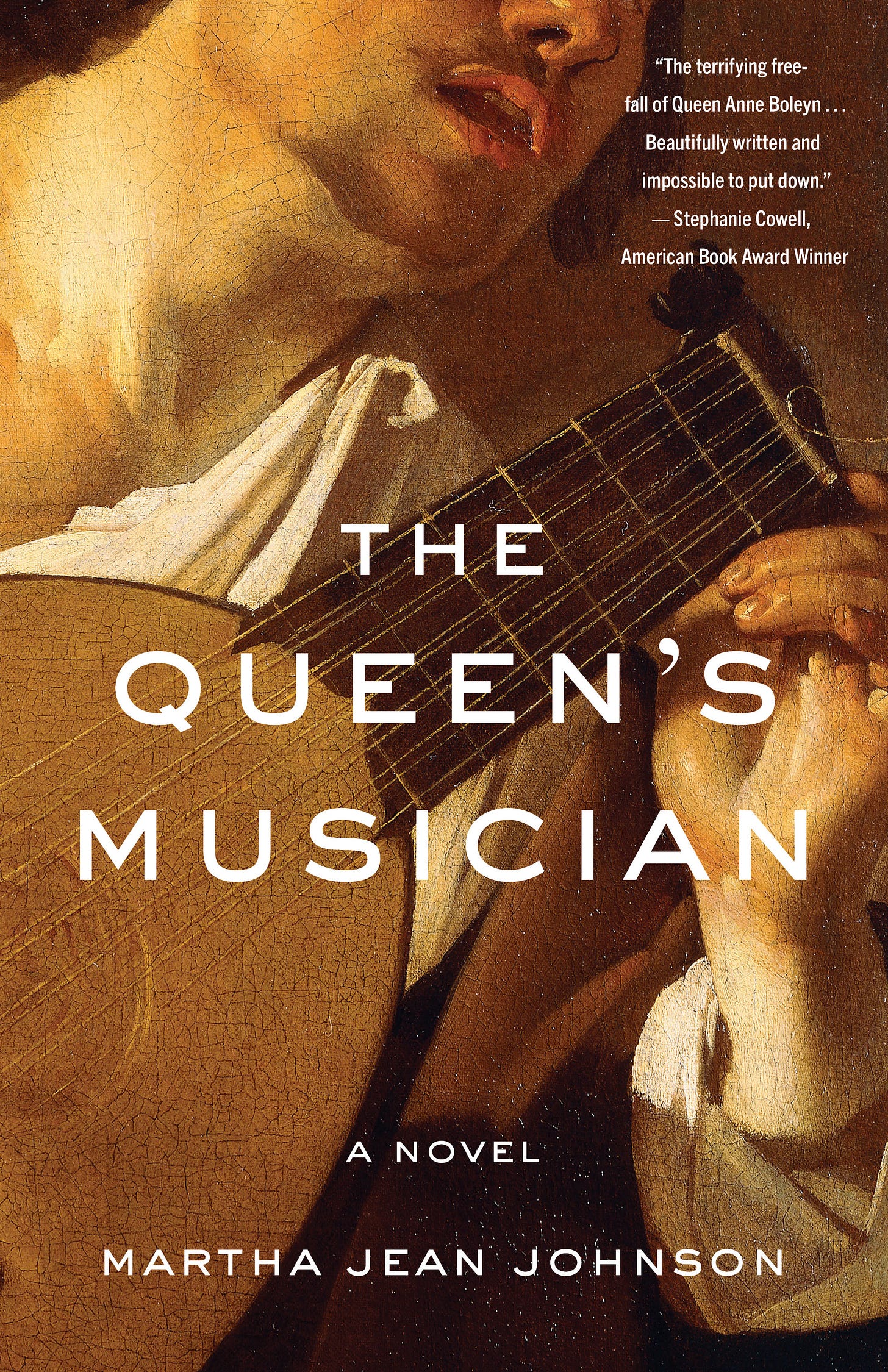

The Queen’s Musician, my own forthcoming novel, depicts a well-known tale. Anne Boleyn’s tragedy is infamous. Anyone who follows the Tudors knows that Henry VIII and Thomas Cromwell had several men executed for adultery with the queen. My protagonist, Mark Smeaton, is one of them. His death at the end is inevitable. And even if readers don’t know the particulars, the back cover gives them the gist.

So why would anyone take the time to read a novel when they already know the end? Here are some reasons.

Familiarity doesn’t breed contempt.

Looking at recent mega-hits, you might think surprise endings are be-all-and-end-all of reader satisfaction. But psychological studies suggest that most people actually “enjoy a story more when they know how it ends.” Researcher Jonathan Leavitt explains that knowing the outcome allows readers “to make better inferences [and] ultimately understand the story better.” Maybe a little foreknowledge frees us up to focus on other elements—the characters, the setting, the dialogue, the themes. Speaking for myself, I often choose novels about well-known events because I dislike books where “not much happens.” If there’s a name brand crisis or tragedy or triumph within the plot, I’m more confident I’ll find it interesting.

Lack of surprise doesn’t mean lack of suspense.

Surprise and suspense are often used interchangeably, but Alfred Hitchcock distinguished between them. Hollywood’s “master of suspense” described two scenes that might occur in a movie. In one, people are sitting around a table, and suddenly, there’s an explosion. The audience is surprised and shocked. In the second, people are sitting around a table, and the viewer knows there’s a bomb underneath. Naturally, the tension builds. The first situation is more surprising, but the second has more suspense. Of course Hitchcock often delivered on both counts—I’d say Psycho is both surprising and suspenseful.

The outline isn’t the story.

We often know the high and low points of historical events and famous lives. We have a crisp little adage summarizing the destinies of Henry VIII’s six wives—divorced, beheaded, died, divorced, beheaded, lived. We know Beethoven lost his hearing and that Napoleon was defeated at Waterloo. But these bits of information omit a huge swath of dramatic potential. They rarely shed much light on the human beings. They can’t explain what these individuals were thinking and why they did what they did. Novelists can sift through the unknowns and theorize about “what really happened.” Since no one has the definitive answers, novelists keep hypothesizing, and readers keep on reading.

New vantage points breathe life into old stories.

In recent years, a number of historical novels have revisited well-trodden territory from fresh perspectives, often those of women and minorities. Maggie O’ Farrell’s Hamnet gives Shakespeare’s wife her own voice. The immortal bard barely shows up. Louis Bayard’s brilliant The Wildes recounts Oscar Wilde’s disastrous fall from his family’s point of view. Most of us are appalled by the playwright’s wrenching story, but how many of us have considered its impact on his wife and sons? Terri Lewis’s Behold the Bird in Flight takes place in a society dominated by powerful men, but it’s a young girl’s tale. The plot revolves around the marriage of England’s notorious King John with twelve-year-old Isabelle of Angoulême. More to come on this one soon.

We get engrossed in “the how.”

In most murder mysteries, the detective (professional or amateur) looks for an unidentified killer, and readers try to guess who it is. But one beloved TV series opens with the killer committing the crime. Lieutenant Columbo generally figures it out right away. These shows aren’t whodunits. We watch to see how the rumpled detective will trap the culprits and deftly reel them in. There’s often a similar dynamic in historical fiction. The facts, the time lines, the bios, the conventional wisdom—these are just the starting point. The magic comes from the “the how.”

What makes a good read

Historical novels aren’t always bereft of surprise. Some feature entirely new stories within a historical context. Some explore events and figures that history has ignored. And even when history determines the plot, writers rely on the ideas above. They build in suspense and new perspectives. They zero in on the how and why.

Like most readers, I enjoy surprise endings, but they aren’t a requirement for me. I saw the movie version of Conclave first, and the ending was definitely a “wow.” But a few weeks later, I read the novel, and I was still riveted. I knew what was coming, but I turned the pages eagerly. The second time around, I had time to savor the setting, a world so different from mine. Since I knew who would win the fictional papal election, I could settle back and let myself enjoy Harris’s characters and skillful storytelling.

For The Queen’s Musician, I never planned to deliver an astonishing twist in the final chapters. It just wasn’t in the cards. My goal was to invite my readers to see Mark Smeaton as a full human being rather than a historical footnote. If you read my novel, I doubt you’ll be surprised by his tragedy, but I hope you’ll grieve for him.

So over to you. Do you enjoy novels that tell a well-known story? Are spoiler alerts important to you? Other thoughts or comments? I love hearing from you.

PUB DATE: MAY 27, 2025. AVAILABLE FOR PRE-ORDER NOW.

A glamorous queen, a volatile king, a gifted musician concealing a forbidden romance. Everyone knows Anne Boleyn’s story. No one knows Mark Smeaton’s.

Kirkus Reviews

“Original and worthwhile . . . A thoughtful, dramatically gripping work of historical fiction.”

Historical Novel Society

“We know how it ends, but the journey is hopeful, bittersweet, and utterly heartbreaking. Highly recommended for anyone who loves Tudor history or anyone who, like me, enjoys being completely destroyed by a story.”

Open Letters Review

"Superb writing and soulful characterization . . . The Queen’s Musician offers a gripping tale for Tudor fans and newcomers alike."

Five Stars from Readers’ Favorite

“In one of the most savage moments in history . . . a heartfelt and thoughtful tale of the fragility of love. Very highly recommended.”

Five Stars from Whispering Stories

“The background research necessary to weave together fact and fiction has been extremely well done . . . The scene-setting was excellent.”

BookLife

“Little is known about Mark Smeaton beyond his tragic fate. Yet Johnson imbues him with depth and dignity, transforming a historical footnote into a fully realized character whose story lingers long after the final page.”

Helene Harrison, Tudor Blogger

“A brilliant book which captures the uncertainty and fear of the late 1520s and 1530s . . . an emotional story told very skillfully.”

Stephanie Cowell, author of The Boy in the Rain and Claude & Camille

“In the terrifying free fall of Queen Anne Boleyn . . . innocent men will be condemned. . . . Beautifully written and impossible to put down. I had tears in my eyes.”

Claire Ridgway, author of The Fall of Anne Boleyn: A Countdown

"A captivating and deeply moving retelling of Anne Boleyn’s dramatic fall . . . This beautifully written novel brings history to life with such emotional depth that it brought me to tears."

Real life doesn't revolve around plot twists, and the ending is only occasionally all that surprising. And I'm still interested in life!

Also, I often read the end of a book first, so I can settle in comfortably to read everything leading up to it!

Absolutely. The most well-known stories can be told in unique ways, and in the hands of a good writer, long-dead historical figures who are names in biographies (or these days Wikipedia articles) become real people. The fun of reading fictional portrayals of historical events is to see how the author brings these people to life through words and fleshes out their thoughts and motivations, and sometimes, I've read novels where the characters are so engaging I find myself hoping, despite knowing how the story ends, that this time, just this once, Catherine Howard or Lady Jane Grey (or anyone else who in real life died tragically) makes it out alive.

The first time I remember being consciously aware of the fates of Henry VIII's wives was in my early teens. When I was about 15, I picked up a novel about Anne Boleyn's rise and fall, which not only ignited a fascination with her story, but introduced me to Mark Smeaton for the first time. A handful of the several hundred pages focused on him: he was depicted as a teenage prodigy recently arrived at court who developed a crush on the Queen and whose life was regarded by more powerful men as expendable. The author's portrayal was so vivid, especially the horrific scene of his interrogation, that I remember some sentences verbatim decades later. I still remember the shock of finding out what happened to him, and my anger at the injustice. And yes, I - a teenager reading about him 450 years after his death - grieved for him. I realised he had a family, friends, perhaps someone he hoped to spend the rest of his life with. Their grief would have been immeasurable. I've been fascinated by him ever since, which has only been fuelled by the way in which some people portray everything they assume he did in a negative light, simply because a traumatised young man who did nothing wrong did not respond under interrogation in the way they (from the safety of their 21st century lounge rooms) think he should have.

I've always thought he'd make a brilliant subject for a novel (or film) so I was delighted to find out about yours!