On June 15, 1215, England’s King John put his seal on a document listing laws he agreed to follow. The signing of the Magna Carta. An undeniably historic day.

I first heard about it in grade school where my teachers told an exciting story about a cruel king who was forced to accept the rule of law. Our school books included colorful pictures: Runnymede, banners waving, the king holding a quill. My high school lessons were less dramatic. We studied the Magna Carta’s influence on the U.S. Constitution and the legal principles based on it.

And I recently read Terri Lewis’s Behold the Bird in Flight. It’s the kind of terrific historical fiction that gets me thinking about the real life events behind it. The novel’s fascinating protagonist is King John’s queen, Isabelle of Angoulême, but its pages vividly capture the cornered monarch. He’s cash-strapped and anxious, perpetually warring with the French and fighting off contenders for the throne. As his fortunes decline, he becomes more sinister and suspicious. In the novel, the Magna Carta comes up near the end:

“When John could no longer defy his barons, he went to Runnymede and signed the Magna Carta, guaranteeing to uphold the ancient laws, affirming the right to trial, to widows’ dower, to reasonable taxes. But for Isabelle, sent to Gloucester for the birth of her fifth child, the Great Charter changed nothing. And shortly, John reneged. The barons raged; the pope was brought into the fray. War would come.”

What an intriguing paragraph! Unlike my teachers, Lewis’s sentences suggest the chaos, doubt, and sheer messiness of this epochal “event.”

1. The king immediately broke his word. Some say he never had “the slightest intention of keeping to Magna Carta.”

2. Revolts and battles erupted, bedeviling the last year of John’s life.

3. His son, Henry III, accepted the Magna Carta, but the journey was convoluted and prolonged. Since Henry was only nine when his father died, a king’s “council” altered and reissued the Magna Carta. Divisions and disputes continued.

4. Once Henry reached his majority, he agreed to the definitive 1225 version. History’s watershed moment actually took ten years.

A Historian Helps Me Out

Given all the twists and turns, I decided to get some perspective from an expert. My guest is the wonderful Sharon Bennett Connolly. She’s a Fellow of the Royal Historical Society and the best-selling author of seven historical non-fiction books, including Ladies of Magna Carta. Her extensive study of the Middle Ages includes an in-depth look at women’s lives, and I’ll be returning to this aspect of her work in a future post.

Here are my questions and Sharon’s answers:

1. If you could teach the next generation just one lesson about the Magna Carta, what would it be?. Are there misperceptions or myths about it that you would like to correct? Do you think it receives the attention it deserves in our history?

“One lesson for the next generation would be that the 1215 Magna Carta was not the definitive charter that established the rule of law in England from that moment on. Magna Carta was an ongoing process, edited, reissued and redefined on numerous occasions in the 13th century. It was actually a peace treaty, between the king and the rebel barons, designed to prevent civil war. And it was a failure, initially. The First Barons’ War broke out within weeks.

But Magna Carta did one very significant thing. It established the principle that no one was above the law, not even the king.

The common misconception is that John is often credited with issuing Magna Carta. You get comments like, ‘he did a lot of things wrong but at least he created Magna Carta’. He didn’t. It was written and issued in his reign—but by John’s enemies. It is a list of the grievances held against him, a condemnation of the areas of mismanagement and abuse of power perpetrated by John’s administration. John was writing to the pope to get it rescinded even before the wax seals had hardened.

Does it get the attention it deserves? I don’t think so. It is the most significant piece of legislation we have in England. It is the closest thing we have to a written constitution and the foundation of our criminal justice system. And I can’t count the number of constitutions and legal systems around the world that have used Magna Carta as their inspiration. It is now over 800 years old and still relevant, even though only 4 of its original 63 clauses are still in use today.”

2. King John is often depicted as an outright villain. Do you think he was worse than other rulers of the era? Should history’s judgment of him be amended or corrected in any way?

“I am considering writing a new biography of King John. History has painted him as an outright villain. And he did do bad things, but so did his brother, Richard I, and his father, Henry II, but they don’t get as bad a press. That is mainly because they kept the church onside. John had a very fractious relationship with the church and, as a result, the chroniclers [describe] every bad thing he did. He also was not as good at war as Richard was, so there was no glorious reputation for him to hide behind. I’m not saying he didn’t have his faults, but I do think it’s time he was looked at with a little less bias.”

I do hope Sharon writes about King John because, to quote Wikipedia, he “has been portrayed many times in fiction, generally reflecting the overwhelmingly negative view of his reputation.” The Wikipedia post has a fun list of his “cultural depictions” including the Errol Flynn and Disney versions of The Adventures of Robin Hood.

Just words?

For me, the most remarkable aspect of the Magna Carta is that the barons decided to list their demands rather than just killing John and putting a new guy in his place. They prepared a document—about 3500 words—that became “the foundation of constitutional liberty in England.” They pinned their hopes for change on the law, not on a single human being.

But there’s another lesson, isn’t there? In Sharon’s words, the Magna Carta “was a failure, initially.” The ten-year drive to codify it was tumultuous. I wonder how many times its advocates thought of giving up. Too dangerous. Too frustrating. The king’s a liar. You can’t trust anyone. This is hopeless.

Luckily for us, at least some of them refused to quit.

Over to you now. Do you see any parallels in the fight for the Magna Carta and the challenges and questions we face today?

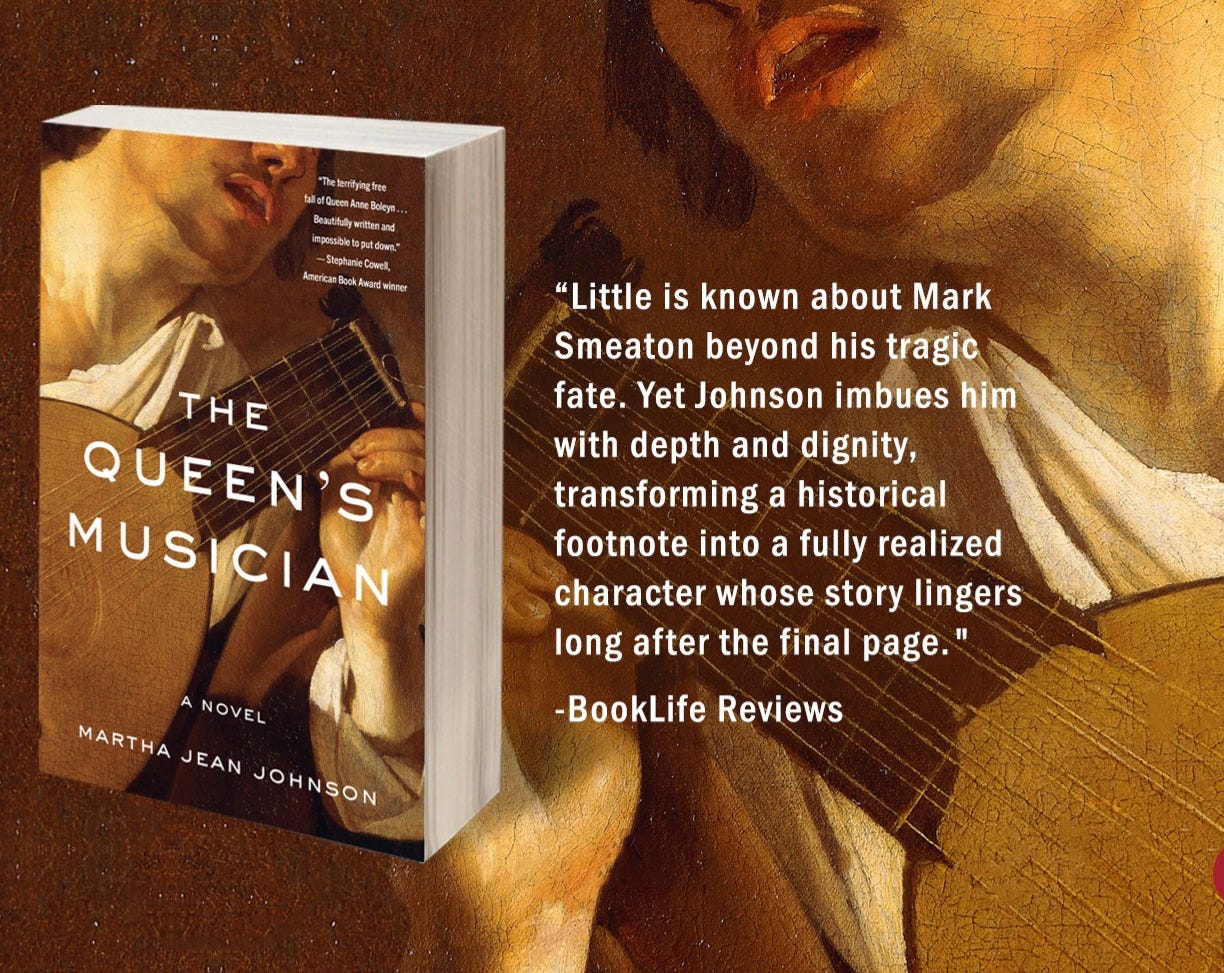

Open Letters Review

“Superb writing and soulful characterization . . . The Queen’s Musician offers a gripping tale for Tudor fans and newcomers alike.”

Historical Novel Society

“We know how it ends, but the journey is hopeful, bittersweet, and utterly heartbreaking. Highly recommended for anyone who loves Tudor history or anyone who, like me, enjoys being completely destroyed by a story.”

Midwest Book Review

“Original, clever, deftly crafted, engaging . . . a 'must' for fans of historical novels set in the Tudor/Renaissance era . . . riveting and memorable.”

Kirkus Reviews

“Original and worthwhile . . . A thoughtful, dramatically gripping work of historical fiction.”

Five Stars from Readers’ Favorite

“In one of the most savage moments in history . . . a heartfelt and thoughtful tale of the fragility of love. Very highly recommended.”

Five Stars from Her Grace’s Library

The characters are vibrant and deeply human . . . Johnson excels at making readers care about them, drawing us into a world where we already know the outcome, but nonetheless making us hope for a minute before slowly shattering our hearts.

Five Stars from Whispering Stories

“The background research necessary to weave together fact and fiction has been extremely well done . . . The scene-setting was excellent.”

Available where books are sold.

Read a recent interview with me about the book at Dead Darlings/Everything Novel.

I see numerous similarities and wonder what Wikipedia will publish about Donald Trump.

I love how you find fresh angles on history.

I wonder: is this the seed of your next book?