Turning to History to Send a Message

Witch hunts, revolutions, and 1950s TV offer parables for our time

How do historical fiction writers choose their subjects? How do they pick a particular story to tell?

Many have a long-standing fascination with a specific era—they enjoy writing about ancient Rome. Some explore the biographies of historical figures who intrigue them—what were these individuals really like? Others delve into daily life in tumultuous times—how did people make it through? Nearly all historical fiction contains some political or social commentary, but it’s often a by-product. It flows beneath the surface.

But sometimes writers choose subjects because they want to make a political statement. The moral of the story is paramount. Look at what happened in the past, these writers tell us. Let’s take a lesson from it.

Here are some examples I’ve encountered lately, and I recommend all of them if you’re not already familiar with them.

Good Night, and Good Luck by George Clooney & Grant Heslov.

I recently saw Good Night, and Good Luck on Broadway. The title comes from the closing line in Edward R. Murrow’s news broadcasts. George Clooney plays the legendary journalist.

The setting is the early 1950s—gray-suited men smoke cigarettes in a mid-century TV studio. The drama centers on a relatively short period in Murrow’s career—his clash with Senator Joseph McCarthy. McCarthy was on a rabid hunt for clandestine communists in the U.S. military, government, and Hollywood. His reign of intimidation was a shameful episode in American politics.

In the play (and in history), Murrow decides to expose McCarthy’s lies and distortions, and his co-workers join him in the fight. After his show airs a segment consisting almost entirely of McCarthy’s own words, Murrow loses his program sponsor and prime time broadcast slot. In those days, you didn’t go up against McCarthy without risking your career. Good Night, and Good Luck is a hero’s journey, and in the end, truth and decency prevail.

Theater goers are flocking to see this play, and applause erupts repeatedly during the performances. I’ve been to Broadway shows where the audience starts clapping the moment a glittery Hollywood star appears onstage, but that’s not what’s happening here (although Clooney is very good). Instead, people react to lines that seem to apply to today’s politics. They clap because they want truth to triumph over deception. They applaud those with the courage to resist a bully.

The Crucible by Arthur Miller

Miller was a successful playwright when McCarthy began hunting for hidden communists in Hollywood. The writer watched in disgust as the senator destroyed the livelihoods and reputations of those he targeted, no matter how slender or preposterous the evidence. Miller later described his mindset: “I began to despair of my own silence.”

But rather than craft a story about 1950s Hollywood, Miller wrote a play about 17th century Salem, Massachusetts. I recently watched the film of The Crucible for an online course on witch hunts in England and Scotland led by the amazing Tudor scholar, Claire Ridgway. The history is fascinating and horrifying, and it’s deeply thought-provoking.

The Crucible begins when several young girls claim they’ve been bewitched—there’s a tiny knot of hysteria. But panic spreads as neighbors begin accusing neighbors. In the end, nineteen people are convicted and hanged as witches. One man is pressed to death for refusing to enter a plea.

Like many authors, Miller exercised creative license. In his script, a young woman named Abigail Williams wants John Proctor to leave his wife for her. When he refuses, she accuses his wife of being a witch. There’s no evidence this happened: Proctor was 59 when he was hanged. Abigail Williams was just 11. Historians don’t really know why the Salem witch hunt began.

But Miller is going for a deeper truth. In this small colonial town, fear was so contagious it stamped out reason. Compassion vanished as people gathered to watch their neighbors hanged.

Writing for New England Historical Society, Emerson Hurley points out the shrewdness of Miller’s decision to write about Salem: “When we look closely at the histories of the European witch hunts and the American Red Scare, we find a number of striking similarities . . . Miller’s astute recognition of this uncanny resemblance is an important part of what makes The Crucible so intelligent.”

A Tale of Two Cities by Charles Dickens

In the nineteenth century, Dickens gave us heartbreaking images of poverty alongside indelible portraits of greed. He set most of his plots in his own time. But in 1859, he wrote his classic novel about the French Revolution which had begun some seventy years earlier.

The French had rebelled after centuries of appalling mistreatment by the nobility. In Dickens’ plot, a doomed romance unfolds against scenes of the rebels’ furious vengeance against the upper classes accompanied by the whoosh of the guillotine.

As one critic put it, Dickens looked to the past and saw “similar dynamics at work in the English scene. . . . The Industrial Revolution had confined many workers to drudgery and injustice and ignorance [while] the upper classes went on indifferently with their lives.” Dickens used the bloody French Revolution to show how abuse breeds abuse and how being brutally exploited erodes the human heart.

Richard III by William Shakespeare

You could argue that Richard III was Shakespeare’s first really excellent history play. It followed three works about Henry VI which haven’t aged all that well. But Richard of Gloucester was next in line, and the immortal bard imbedded a political message within the drama. As an Elizabethan, he valued stability. As a playwright, he aimed to please.

He lived in an era when plots to steal the crown were regular occurrences. Elizabeth I faced a string of such conspiracies. But it’s also true that her own family’s reign began in violence. Richard III, England’s last Plantagenet king, lost the crown to Henry Tudor who defeated him at the Battle of Bosworth Field. Despite an underwhelming hereditary claim to the throne, Henry became Henry VII, the first Tudor king.

For the Tudors, it was an article of faith that Richard was a tyrant who fully deserved his fate. Elizabeth I was a rightful queen. Shakespeare legitimized her rule by depicting Richard as a monster. As one source notes, “Shakespeare did more than simply rehash Tudor propaganda. He took the legends surrounding Richard and embellished them to create a villain of mesmeric power and blackness.”

Many historians today doubt that Richard was as evil as Shakespeare portrays him, but the play is making a point: This guy was really bad. We’re lucky he was overthrown.

Plus, my bet is that Shakespeare enjoyed adding his own dollop of wickedness to Richard’s character. Creating despicable villains is the literary equivalent of catnip.

My admiration and a caveat

I admire writers who use their dramatic gifts to help us remember history and keep its lessons in mind. Works like The Crucible and A Tale of Two Cities seem to me to be distinctively powerful. They put the people who suffer from our political and social blindness right before our eyes.

But I can easily think of examples gone wrong. Margaret Mitchell probably thought of Gone with the Wind as a profile in resilience. Now we read her novel or see the film with reservations: These works glamorize the “old South” and sugarcoat slavery’s brutality. For me, Oliver Stone’s J.F.K. puts a dangerously attractive gloss on wild conspiratorial thinking. Maybe you would put Richard III in this more problematic category (It’s still an incredible play).

And of course, novelists and dramatists are hardly alone in periodically misusing history. Go online or turn on the TV. Politicians and social media denizens do it regularly.

Now I hand the mike to you. What’s on your mind? What do you think of my examples and my caveats?

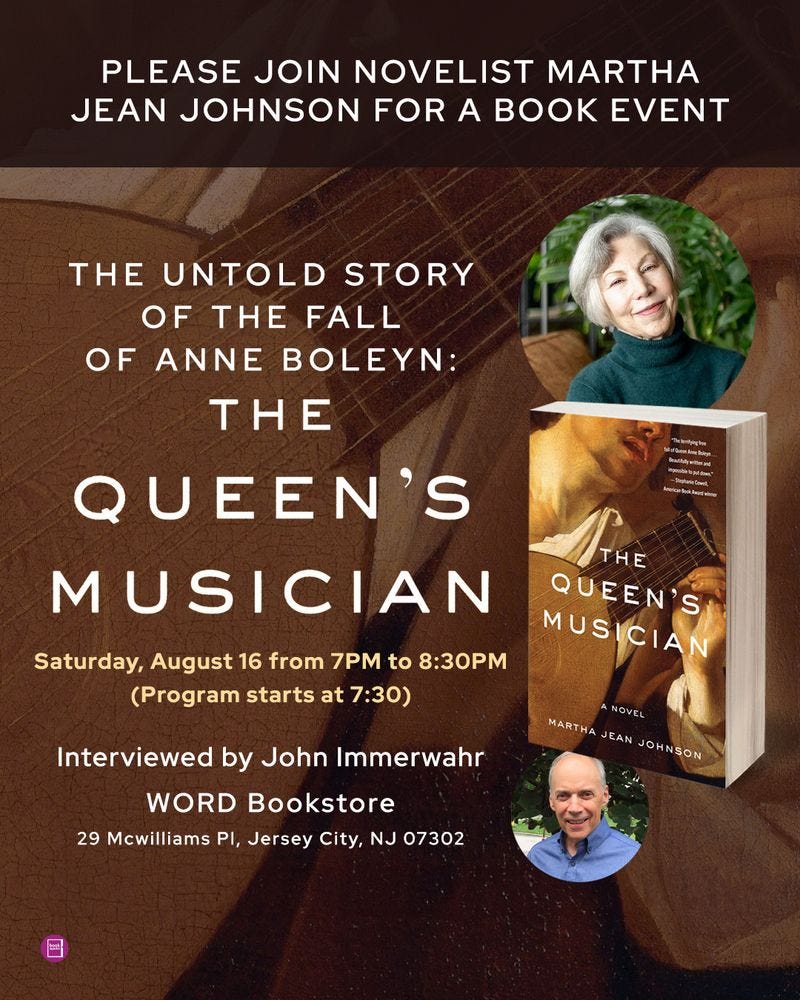

THE QUEEN’S MUSICIAN IS AVAILABLE NOW.

A glamorous queen, a volatile king, a gifted musician concealing a forbidden romance. Everyone knows Anne Boleyn’s story. No one knows Mark Smeaton’s.

On May 17, 1536, a young court musician was executed, accused of adultery and treason with the queen. Most historians believe both he and Anne Boleyn were innocent—victims of Henry VIII’s rage.

Kirkus Reviews

“Original and worthwhile . . . A thoughtful, dramatically gripping work of historical fiction.”

Historical Novel Society

“We know how it ends, but the journey is hopeful, bittersweet, and utterly heartbreaking. Highly recommended for anyone who loves Tudor history or anyone who, like me, enjoys being completely destroyed by a story.”

Open Letters Review

"Superb writing and soulful characterization . . . The Queen’s Musician offers a gripping tale for Tudor fans and newcomers alike."

BookLife Reviews

“Little is known about Mark Smeaton beyond his tragic fate. Yet Johnson imbues him with depth and dignity, transforming a historical footnote into a fully realized character whose story lingers long after the final page.”

Five Stars from Readers’ Favorite

“In one of the most savage moments in history . . . a heartfelt and thoughtful tale of the fragility of love. Very highly recommended.”

Five Stars from Whispering Stories

“The background research necessary to weave together fact and fiction has been extremely well done . . . The scene-setting was excellent.”

Helene Harrison, Tudor Blogger

“A brilliant book which captures the uncertainty and fear of the late 1520s and 1530s . . . an emotional story told very skillfully.”

Stephanie Cowell, author of The Boy in the Rain and Claude & Camille

“In the terrifying free fall of Queen Anne Boleyn . . . innocent men will be condemned. . . . Beautifully written and impossible to put down. I had tears in my eyes.”

Claire Ridgway, author of The Fall of Anne Boleyn: A Countdown

"A captivating and deeply moving retelling of Anne Boleyn’s dramatic fall . . . This beautifully written novel brings history to life with such emotional depth that it brought me to tears."

JERSEY CITY FRIENDS AND NEIGHBORS:

You can pick up a copy of The Queen’s Musician at our beautiful local bookstore, WORD at Hamilton Park. And we’ll talking about the novel and all things Tudor come August 16. Please join us if you can.

Talking into the mike, I would say that I like those writings that offer a fresh lens to look at historical events. I rather suspect that I am going to like the Queen's Musician for this reason. I read a couple of pieces in the journal, The American Scholar, this morning that are examples of what I mean. The first was a consideration of the actual number of deaths attributed to the Civil War, and how what we have been taught is likely pretty far off, because of the difficulties in recording the numbers in the mid 1860s as well as the lesser attention paid to the loss of enslaved people across this time. The second article was by a Flannery O'Connor scholar whose recent investigations have identified a Black woman, Emma Jackson, who worked as a maid and nanny for the O'Connors in Flannery's earliest years in Savannah. The author contends that what she is learning about the relationship of Flannery to this woman may contribute to deeper understandings of Flannery's fluctuating views on segregation and integration.

There's also a fine movie version of "Good Night..." starring Clooney and David Strathairn as Murrow. Both the film and the play were co-written by Clooney.

Another fascinating post Ms. Johnson