In real estate, the rule is “location, location, location.” Location is the chief factor determining a house’s value, not whether it has a two-car garage or an attic.

But in fiction, a novel’s setting is just part of the mix. Authors need to deliver engrossing plots, believable characters, and seductive narration, along with interesting settings. Very few readers will stick with a book that only offers ambience.

And yet, I sometimes remember a story’s setting long after I’ve forgotten the plot. I couldn’t begin to tell you all the twists and turns in The Hound of the Baskervilles, but I can still picture the ghostly moors and menacing fog.

This past year, I’ve reveled in the lush natural environments in Tan Twan Eng’s The House of Doors (set in colonial Penang) and Abraham Verghese’s The Covenant of Water (set in Kerala, South India). These authors’ words create luxuriant mental images of places I’ve never been to. Now I want to visit.

Historical novelists often face a particular challenge. They have to describe spaces—cities, towns, buildings, rooms, etc.—that no living being has ever seen. Authors may have historical descriptions, ruins, sketches, or paintings to rely on, but they need to use their imaginations.

Here are three books that bring long lost places to life and tell absorbing tales to boot.

The Decks of a Tudor Warship. Heartstone by C. J. Sansom.

Sansom, who died in April 2024, might well be my favorite historical novelist. He left behind seven wonderful Tudor mysteries—I’ve read and enjoyed them all. His “detective” is lawyer Matthew Shardlake, a decent man in a brutal era.

In one of his adventures, Shardlake boards the Mary Rose, Henry VIII’s storied warship which sank unexpectedly in July 1545. Experts have proposed various reasons for the catastrophe, including enemy cannon fire, poor design, overloading, and human error. In his afterword, Sansom summarized the key facts: “The Mary Rose sank in minutes, with the vast majority of those aboard trapped under the anti-boarding netting [designed to prevent enemy soldiers from jumping onto the ship]. Their screams were audible from the shore. Around thirty-five people survived out of, it is now estimated, 500.”

In the novel Heartstone, Shardlake visits the warship just before the tragedy. “It had been night when I boarded her,” he reports, “but now, in the fading daylight, I could see how beautiful she was, as well as how massive: the powerful body of the hull, the soaring masts almost delicate by contrast; the complex web of rigging where sailors were clambering; the castles painted with stripes and bars and shields in a dozen bright colours.” Onboard, he describes the narrow passageways, the heavy cannon, the officers and sailors with only hours to live. As you’ve probably guessed, Shardlake survives to appear in subsequent Tudor mysteries.

Seventeenth Century London. The Ashes of London by Andrew Taylor.

The 1666 “Great Fire of London” is the kick-off for Andrew Taylor’s six Restoration era mysteries. His “investigators” are James Marwood, a royal clerk and spy, and Cat Lovett, a fiery, dispossessed heiress. These books provide all sorts of thrills and puzzles, but Taylor’s descriptions of seventeenth century London give them their distinctive style and depth. He juxtaposes the city’s grand palaces and elegant townhouses with its reeking streets and seedy taverns.

The first mystery opens with Marwood watching the old St. Paul’s Cathedral burn to the ground: “The fire followed its own logic, not man’s. Streams of molten metal were now oozing between the pillars of the portico and down the steps of the cathedral. It was a thick silver liquid, glinting with gold and orange and all the colours of hell: it was the overflow of the lead pouring from the burning roof to the floor of the nave. Even the rats were running away.” As the plot advances, Londoners begin to grapple with the social, economic, political, and human consequences of the devastation. Sir Christopher Wren, the architect of the new St. Paul’s, is a minor character.

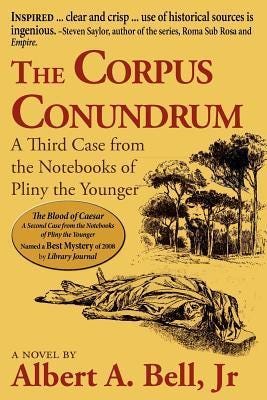

A Roman Villa by the Sea. The Corpus Conundrum by Albert A. Bell Jr.

I’ve been devouring Bell’s Roman Empire murder mysteries, and I’ve just completed my third. For anyone new to the series, Bell imagines the historical figures Pliny the Younger and Tacitus as amateur detectives. So far, Pliny and Tacitus have solved murders in provincial Smyrna (All Roads Lead to Murder) and in the heart of Rome (The Blood of Caesar). Their third case unfolds at Pliny’s villa at Laurentum on the Tyrrhenian Sea. The real life Pliny was one of history’s great letter writers, and he described his vacation home when he invited a friend to visit. Bell, a classics professor, includes his own translation of this letter in an appendix.

In the novel, Bell uses a tried-and-true mystery writer technique—he contrasts the beauty of the surroundings with the ugliness of murder. Pliny introduces the setting: “It was my favorite of the houses I inherited from my uncle . . . I spent some happy days in my childhood here . . . This place possesses a kind of equilibrium of its own, sitting right on the shore but with a large expanse of woods behind it. . . . When I’m here, Rome and its problems might as well be on the frontiers of the empire.” Pliny, Tacitus, and a parade of guests converse in light-filled arcades with mosaic floors and indoor greenery. Visitors enter through a frescoed atrium. Of course, Rome’s cruelty and corruption inevitably creep into this soothing world. There’s not much mystery in an uneventful seaside getaway.

For me, the vibrancy of these skillfully-wrought settings is a gift. The Mary Rose, the old St. Paul’s, and Pliny’ s villa no longer exist, but that doesn’t mean we can’t see them.

I’ll close with two more recommendations:

1. If you enjoy imagining what long lost places looked like, check out author Terri Lewis’ photo-blog on nineteenth century painter Luigi Bazzani. Bazzani captured the ruins of Pompey two centuries ago when they were still saturated with color.

2. And yes, Beatles fans, you’re right. John and Paul wrote my headline: “There are places I’ll remember.” It’s the opening line of “In My Life,” which is number 23 in Rolling Stone’s 2004 list of "The 500 Greatest Songs of All Time." If you have a moment, watch the video. It brought back bittersweet memories for me.

So I turn this one over to you. Can you point us to some novels with settings that have stayed in your mind? How important is setting for you compared to a novel’s other attributes?

?

For me, the setting is a critical element in any murder mystery. It’s like an additional character. If the setting isn’t clear and vivid from the back cover copy I go no further!

Beautifully written, as always.

Among my favorite settings are the scenes in War and Peace, especially Natasha dancing, both at the ball with Prince Andrei and later her folk dance by herself when her family is financially ruined.