A friend who loves historical fiction recommended An Officer and a Spy, but I wasn’t immediately drawn to a plot centered on espionage and the military in fin de siècle France. Now that I’ve read it, I would rank this superb novel about the Dreyfus Affair as one of my top suggestions. First published in 2013, this is a book for this moment. It is cautionary tale about the insidious grip of antisemitism and the easy corruption of ambitious men.

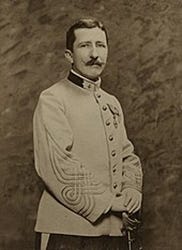

I remembered the Dreyfus Affair from school, but my grasp of the details had faded. The French military falsely accused a Jewish officer of spying for the Germans. Alfred Dreyfus was sent to Devil’s Island. Émile Zola rose to his defense. When I opened the novel, I was unaware that the protagonist, a career soldier named Marie-Georges Picquart, was a historical figure who played a pivotal role in Dreyfus’ eventual pardon.

So what makes An Officer and a Spy great historical fiction?

Harris knows his stuff. His research included trial records, contemporary French and English newspaper accounts, and Dreyfus’ own journals, on top of secondary sources. Wisely, he resists telling us all he knows. Instead, he turns a convoluted, slow-moving miscarriage of justice into an engrossing, tension-filled story. It’s a spy novel but without the gunplay and clever gadgetry. The good guys rely on low-tech, human snooping—they sort through trash and piece together scraps of paper. The book’s settings include stakeouts, courtrooms, and prisons, along with Parisian salons and Alsatian restaurants. Once I entered the novel’s world, I stole every moment I could to return.

Fundamentally, this is the tale of a man trying to right a wrong, but it’s neither simplistic nor artificially amped up. Both Dreyfus and Picquart are courageous and admirable, but neither is a perfect, prettified hero. The villains are French generals and officials who range from the pathetically venal to the utterly cruel. Even the worst is believable, exhibiting a bleakly familiar brand of moral cowardice. For these men, antisemitism is a key motivator, but so is pigheadedness and the desire to hide mistakes. This is, by the way, a novel about men. There are memorable women characters, notably Madame Dreyfus, but the narrative concentrates on the stupidity and valor of men.

For me, historical fiction is exceptional when it sheds light on both past and present. In this novel, France’s top military men persist in backing Dreyfus’ conviction despite proof of his innocence. They stick to their stories long after learning the identity of the actual spy. Some go further, forging documents and perjuring themselves to maintain the lie.

This mindset is instantly recognizable. We see it among American politicians who promote myths of “rigged” elections. We see it when religious, corporate, and university leaders conceal sexual abusers to “protect the institution.” Those who fail these tests of decency are rarely completely evil, but their callousness and collusion cause lasting harm.

What explains this phenomenon? Some people convince themselves they are being pragmatic. Others fear rocking the boat. Some casually adopt the prevalent groupthink and then willfully ignore any inconvenient inklings of truth. Some choose to protect their careers regardless of the cost to their souls. Harris ably captures these attitudes in his dispiriting portrayals of Picquart’s colleagues and superiors.

The novel hooked me in immediately, so I was surprised to read Janet Maslin’s New York Times criticism of “this seasoned and mannerly author” for what she views as the book’s dull and “gentlemanly” start. How does Harris open? Picquart has just observed Alfred Dreyfus’ ritual public degradation at the École Militaire prior to his transfer to Devil’s Island. As ordered, Picquart visits the Minister of War to report on what he has seen—four thousand soldiers on parade, a hushed crowd, the arrival of a horse-drawn prison wagon. “Drums rolled. A bugle sounded. An official stepped forward, holding a sheet of paper up high in front of [the convicted man’s] face.” Dreyfus declares his innocence before a sergeant major rips the gold braid and buttons from his uniform. As Picquart describes the event, the Minister of War asks about the size of the crowd. I’ve grappled with decisions about where to begin a novel myself. I thought Harris’ choice was brilliant.

An Officer and a Spy depicts the ups, downs, and detours of a long battle for justice. I read it with a painful sense of watching deceit and bigotry triumph. Only a handful of individuals had the courage to speak up for Alfred Dreyfus. Yet in the end, they won.

Reminding us of humankind’s capacity for error (and correction) is one of historical fiction’s gifts. This excellent, readable novel based on the factual record reminds us of what happens when spinelessness and self-interest blot out the truth. It also reminds us that big lies can be defeated.

Martha is a formidable writer who immediately grabbed my interest in her description of An Officer and s Spy

The relevance to current issues is compelling.

and has made me want to read it immediately

I am looking forward to her next blog post.

It is a real treat.