My Tribute to C. J. Sansom (1952 - 2024)

A master of historical fiction—from the Tudors to World War II

British novelist C. J. Sansom died on April 27, 2024. This superb literary craftsman began writing fiction in his forties and completed nine best-selling, prize-winning novels. I’ve read eight and consider them among the most enjoyable historical fiction I know.

Sansom’s books tell meaty, twisty tales that immerse you in the past. As The New York Times’ Trip Gabriel put it, he lets you “eavesdrop on women arguing in a market stall and inhale the stench of London streets.”

Sansom is best known for his Tudor detective mysteries which are rich in political intrigue and mercifully light on the doublets and the jewels. Here’s a quick overview:

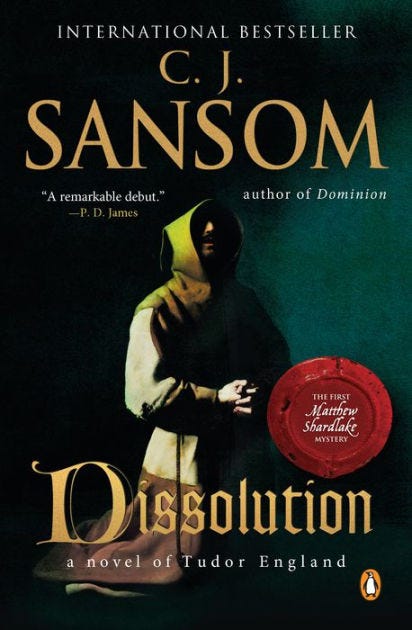

Dissolution introduces his solitary protagonist, Matthew Shardlake, a lawyer and part-time investigator for Thomas Cromwell. On orders, Shardlake travels to a seaside monastery where a government agent has been murdered. It’s the “dissolution of the monasteries,” and Cromwell is working to expose “corrupt” brotherhoods so he can confiscate their wealth. Even at the outset, Shardlake is ambivalent: “Once the prospect of . . . talking with [Cromwell], seeing [him] at the seat of power . . . would have thrilled me, but this last year I had started to become weary, weary of politics and the law, men’s trickery, and the endless tangle of their ways.”

Shardlake is humane and conscientious, and also a “hunchback”—the word others use to denigrate him.

Dark Fire is set in 1540 when Cromwell’s power is slipping. This time, Shardlake is hunting for the missing formula for “dark fire,” a dreaded weapon of war. He is also trying to prevent the execution of a young woman accused of murder. He has twelve days to solve both problems. I always love a countdown novel. Dark Fire introduces the rakish Jack Barak, Shardlake’s intrepid assistant. By the book’s end, Cromwell “has fallen off the tightrope of the king’s pleasure at last.” It is left to Barak to describe the beheading.

The next three mysteries, Sovereign, Revelation, and Heartstone, combine murder, politics, thrills, and trickery. Each depicts a different historical event including Henry VIII’s Progress to the North, the sinking of his famed warship, the “Mary Rose,” and the entrances and exits of several of his queens.

The plots are not all politics and investigation. Sansom’s stories touch on the human element as well. In Sovereign, a subplot follows the young Catherine Howard who has a reckless flirtation (and perhaps an affair) with a handsome courtier. Shardlake later hears about the young queen’s death: “They said in London [that] she had been too weak with fear to mount the scaffold unaided . . . Poor little creature, she must have been so cold, there on Tower Green, with her head and neck exposed for the executioner.”

Revelation involves a series of grisly deaths that mimic the Biblical apocalypse. Even when the case is solved, Shardlake struggles to comprehend the mind of the killer: “I cannot fathom why he did these things. At the end he seemed confused, deranged, wild—not the calculating creature I expected.”

It’s no spoiler to reveal that Heartstone ends with the sinking of the “Mary Rose.” As The Independent’s Jane Jakeman notes, “Sansom brilliantly exploits the hindsight that we bring to the historical novel, for we turn the pages with bated breath, waiting for the inevitable, wondering who will survive. Life aboard the ship, top-heavy, crowded with soldiers and sailors, is rivetingly described.”

I still can’t decide which of Sansom’s last two Tudor mysteries is my favorite. In Lamentation, an ailing but volatile Henry has married Katherine Parr in an era of religious fanaticism. The real life Katherine wrote about her faith in a text titled “The Lamentation of the Sinner.” To some, her beliefs were heresy, and the document wasn’t published until after Henry’s death. In Sansom’s novel (though not in real life), the queen’s enemies have stolen the Lamentation with plans to disseminate it broadly—an act that would enrage the king and doom the queen. She calls on Shardlake to retrieve it before it can be printed.

Tombland is Sansom’s last book, and it is ideal historical fiction. Henry is dead, and Shardlake’s client is the young Princess Elizabeth. A bizarre murder leads to a motley assortment of suspects, including a lesser-known Boleyn. The plot unfolds during Kett’s Rebellion, a historical revolt against predatory landowners that was quickly crushed by the crown. Shardlake and Barak aid the insurgents who naively believe the government will hear and address their grievances. Sansom delivers a rich, pulsating picture of the rebellion, from its hopeful early days to its heartbreaking end.

Sansom wrote two non-Tudor novels: Dominion—an intriguing alternative history in which the Nazis conquer Britain—and Winter in Madrid, which I have not read. I find it bitter-sweet that I still have one Sansom novel waiting for me.

Here’s what I love about this man’s books:

He seamlessly blends history and storytelling.

No lengthy digressions to recap “the history.” No characters clumsily spouting the pertinent details. His plots are all of a piece. Dusty textbook phrases like the dissolution of the monasteries, the sinking of the “Mary Rose,” and Kett’s Rebellion are comprehensible and tangible. As Tracy Borman writes in her History Extra tribute to Sansom, his novels “vividly [bring] to life . . . the often-devastating impact that these events had on the lives of the ordinary people.”

The protagonist is not some testy genius.

Holmes, Poirot, and Inspector Morse are mesmerizing, but also distant and temperamental. Shardlake toils to solve his cases. He sidesteps treacherous political plots that could spell his death. He’s smart, but also conflicted and lonely. He’s a kind and generous friend.

Sansom admired Katherine Parr.

Most Tudor fans gravitate to one of Henry’s six queens, and for me, it’s Katherine Parr. In addition to outliving her dangerous husband, she was the first English woman to publish a printed book. Sansom depicts her as “sophisticated, beautiful, and profoundly moral.” After Henry’s death, rumors fly that she will finally marry the love of her life, the dashing Thomas Seymour. Shardlake fears for her—Seymour is a philanderer who flirts with treason. Yet in the end, the lawyer detective seeks to understand her: “Perhaps after so many years of duty, [she] felt the right to her own choice.”

I tried to learn from Sansom when I was writing The Queen’s Musician (Pub date: May 27, 2025). He went beyond history’s famous names to delve into the hearts and minds of forgotten figures such as Robert Kett. My book portrays the innocent men executed in the plot against Anne Boleyn. I hope I’ve done well by them.

Hulu’s new TV series, Shardlake, premiered shortly after Sansom’s death. I haven’t seen it, but The Guardian calls it “mean, moody . . . the perfect tribute to its author.” That sounds about right to me. Sansom made history fascinating, but he didn’t prettify it.

I notice that the title of your forthcoming book appears to have changed. How about a blog on book titles.

Terrific. As always. What a graceful writer you are. You words just flow.

Besos