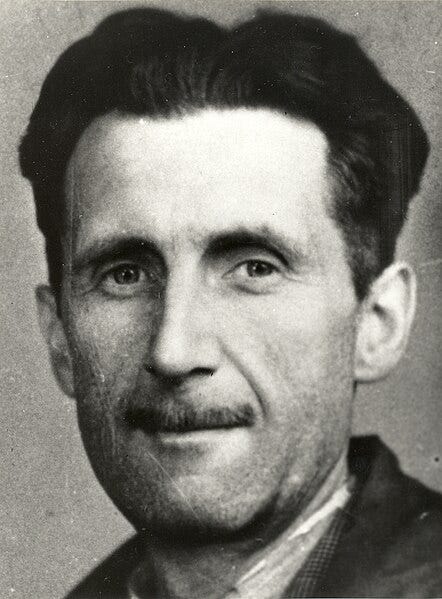

In 1949, George Orwell published 1984 which depicts a totalitarian hellscape ruled by force and fear. He also wrote the allegorical Animal Farm mocking Joseph Stalin and the Soviets. Today, we apply his name to the dangers he warned us about: “mass surveillance, propaganda, rewriting history, the suppression of free speech and independent thought.” We describe them as “Orwellian.”

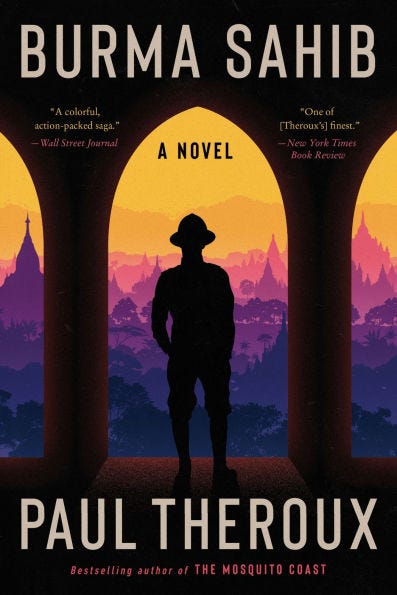

And yet this author known for denouncing oppression was once one of its enablers. Between 1922 and 1927, when Orwell was just out of Eton, he served as a colonial policeman in Burma (now Myanmar). Paul Theroux’s fictional biography, Burma Sahib, imagines this segment of Orwell’s life.

A Slide into Brutality

Theroux envisions Orwell’s transition from malleable young Etonian to colonial functionary to a writer intent on exposing tyranny. Through fiction, Theroux shows us Orwell’s moral and psychological descent. At the time, Orwell still used his family name, Eric Blair. Later, when he began to write and publish, he chose the name we know today.

The novel follows Blair’s arrival in Burma, his police training, and subsequent rural and city postings. Theroux recreates the harrowing incidents that led to Orwell’s later essays, “A Hanging” and “Shooting an Elephant.” But the novel is more than a legendary writer’s coming-of-age story. It pictures a young man’s slide into brutality and his struggle to turn away from it.

Here’s why I recommend Burma Sahib:

It probes an ancient human quandary—why ordinary people become cruel.

As the novel begins, Eric Blair is a socially awkward young man on a ship to Rangoon. He secretly loathes the pretenses of the colonial set he travels with and mostly hides in his room. And yet, over the next five years, Blair will repeatedly try to meet the expectations of these people and their ilk.

Unlike his fellow police trainees, Blair is curious and literate. He’s a serious reader who devours Joseph Conrad and D. H. Lawrence. He makes lists of Burma’s flora and fauna. He learns Hindi and Burmese and admires the local festivals.

And yet, on duty, Blair gradually hardens into an abuser who strikes his servants, harasses monks, supervises whippings, and watches the execution of someone he knows to be innocent. Theroux’s portrait of Blair’s moral corruption is subtle. The young Blair has learned about hierarchy, bullying, and violence at Eton. Starting his professional career, he wants to please his family and satisfy his superiors. He’s afraid of being seen as a weakling, and he faces an age-old question: How low will any of us go as we try to fit in and impress our bosses?

It also suggests the path to change.

Burma Sahib would be a bleak, dispiriting story if its protagonist solidified into the worst version of himself. Instead, Theroux suggests how Blair—sometimes against his own will—grows into a different and better man. As Kirkus Reviews puts it, the novel describes “a Blair whose wounds and offenses and flaws and guilty knowledge are changing him as we watch. The battered, self-loathing man who limps home at the end of the five years is recognizably on the cusp of being Orwell.”

How does Blair break free? There’s no sudden conversion, no “St. Paul on the road to Damascus” moment. Instead, smaller events prick his conscience: An amiable Indian befriends him; the woman he loves rebukes him; he is remorseful after hitting a Burmese schoolboy who jeers at him in a railway station; he suffers a scalding public humiliation that pushes him to reassess his life. A few years later, he will use his own past to warn the world about tyranny’s sadistic core.

Like Orwell, Theroux erases colonialism’s “charm.”

Blair is a lackadaisical colonial from the start. His uniform is never as pressed and spotless as it’s supposed to be. He’s ill at ease in the “bro” culture of the clubs. He cannot avoid seeing what he will later call “the “dirty work of Empire at close quarters.” He questions the way well known authors have painted colonial life: “Kipling dealt in hyperbole and allusiveness . . . the recent Forster novel about India sounded like touristic tosh.”

He secretly begins a novel vowing that “however amateurish his writing [might be], at least it was the truth of the Raj . . . [He] would write of the savagery of the police, the terrified eyes of prisoners, the howls of women widowed by dacoits, the foulmouthed porkers at the club. He would never forget; and someday he’d have a tale to tell.”

Orwell later summed up his rationale for writing: “I write . . . because there is some lie that I want to expose.”

And then there’s Myanmar

Paul Theroux is an acclaimed travel writer as well as popular novelist, and he doesn’t stint on evocative sketches of the land. Blair is the guide, providing rich descriptions of the flowers, trees, sky, and water. Sometimes, he takes joy in the fertile beauty. At other times, he sees the “sadness in the landscape . . . the whole of it otherworldly, marshy, and without definition except for the paddy fields.”

A Triple Play

For me, Burma Sahib is a historical fiction triple play: 1) The story is absorbing; 2) Theroux transported me to a different world; and 3) the novel delves into questions that have been much on my mind of late. Why do good people go along with barbarity? Is there any way to bring them back?

Not long ago, the New York Times published a series of drawings made by Mohammed Farik Bin Amin who was held in a secret “dungeonlike prison run by the C.I.A.” The black-and-white “self-portraits” show him seated in “stress” positions, photographed naked, and held in solitary confinement with a hood over his head. It’s the stuff of nightmares, but it is all-too-real. And yet, throughout history and across cultures, societies have always been able to find men willing to conduct this kind of abuse. Why is that? Is this the way it has to be?

Paul Theroux doesn’t offer an answer, but he does give us a glimpse of how cruelty is inculcated and nurtured. He also shows us how a very young man summons the will to reject it, and that’s worth reading about.

I’d love to get your thoughts on George Orwell, Paul Theroux, and the ideas raised in this book. Why are so many so willing to harm their fellow humans? Is it possible to mend their hearts and minds?

I have read a number of books by Paul Theroux across the years:

The Great Railway Bazaar, Millroy the Magician, Dark Star Safari, Sunrises and Seamonsters are listed in my summer journals, in addition, of course, Deep South.

I really love travel writing, and I would say Dark Star Safari is one of the finest travel books I’ve ever savored. I haven’t read Burma Sahib, but the questions that it raised for you are certainly very similar to ones that have baffled me as well. I cannot grasp deep hatred, cruelty, mad violence, or torture. I’m one of those who opts out of movies where these attributes are illuminated. But the question that I hope you will cause us all to continuously probe is what can cause people to elevate their character and enter a realm where there is a deeply-felt respect for humanity. Does harsh narcissism make this impossible?

Great piece. “Orwell later summed up his rationale for writing: I write . . . because there is some lie that I want to expose.”