A Dazzling Writer's Affair Shatters His Children's Lives

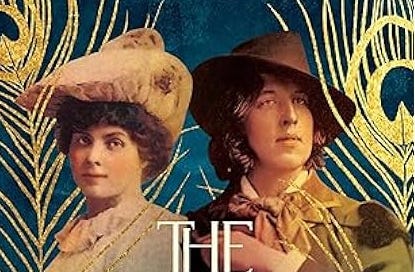

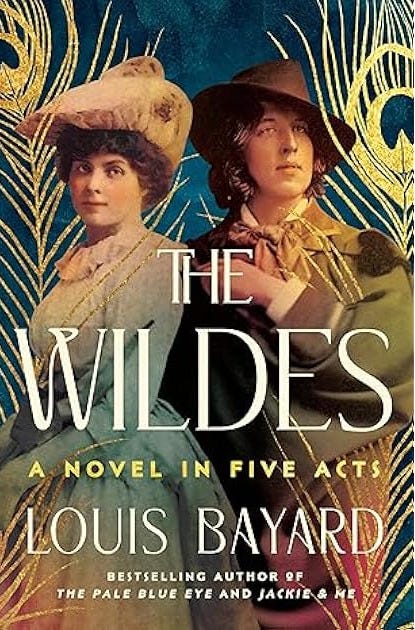

Louis Bayard’s Superb Historical Fiction—The Wildes

The novel begins in a rented country house in England. The year is 1892. A successful author and playwright invites his lover to visit. While his family and other guests enjoy August in Norfolk, the twosome meet in a secret upstairs room. Their hideaway is a “priest’s hole,” a small space created to conceal Catholic clergy during the Protestant Reformation.

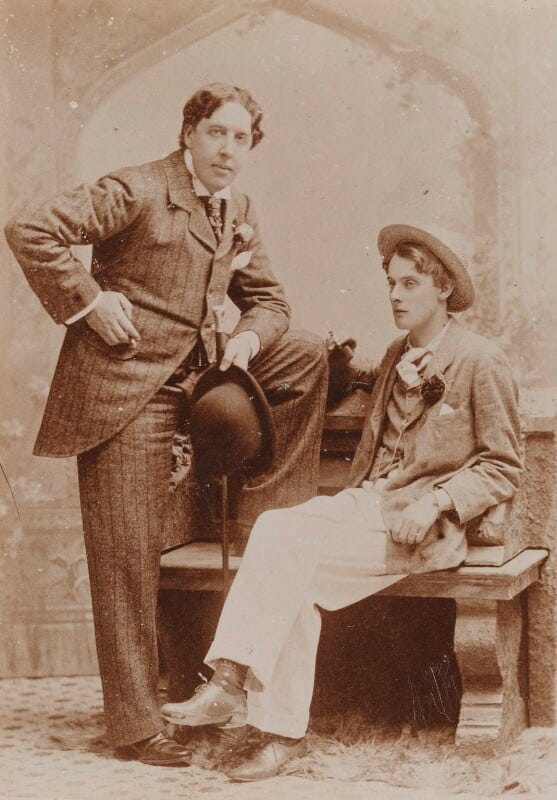

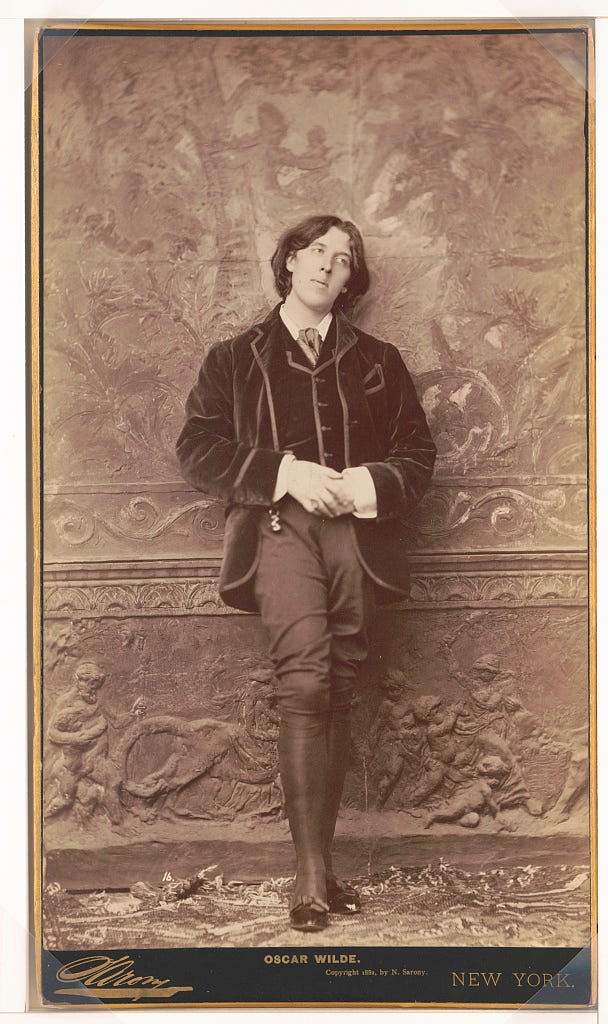

The protagonist’s decision to bring his lover into his household is this novel’s “inciting incident.” The plot unfolds from there. His situation is inherently unstable, and, in this case, particularly precarious: The author is Oscar Wilde. Lord Alfred Douglas is his guest.

Louis Bayard’s The Wildes is an astonishing work. It asks subtle questions about freedom and responsibility. It poses unanswerable questions about love, desire, loyalty, and blame. Bayard’s depictions of Wilde and his wife and children have remained with me since I finished the novel. I suspect they always will.

Here’s what makes The Wildes remarkable and why I strongly recommend it.

It’s not what you expect.

Most readers who begin The Wildes probably assume it will describe Oscar Wilde’s tragedy. This brilliant, witty author was imprisoned for sodomy—Great Britain didn’t decriminalize homosexuality until 1967. The trajectory of Wilde’s life is horrifying. He lost his freedom, his livelihood, his reputation, and his health for engaging in consensual sexual acts. But Wilde’s downfall is not this novel’s focus. Instead, it highlights the collateral damage—the impact on Wilde’s wife, Constance, and his two young sons, Cyril and Vyvyan.

Bayard’s storytelling is original and compelling.

A less-confident novelist might have related the story by describing the family’s reactions at key points in Wilde’s catastrophic descent—when Douglas’ father, the Marquess of Queensbury (or Queensberry), accuses Wilde of sodomy; when Wilde recklessly sues for defamation; when the failed lawsuit reveals evidence that leads to criminal charges; when Wilde goes to prison while his family flees to Europe using an assumed name.

But Bayard mixes traditional storytelling with a sprinkling of documents, allowing these artifacts to speak for themselves. They include:

An 1884 letter from Oscar to Constance. “My soul and body seem no longer mine, but mingled in some exquisite ecstasy with yours.” This is the novel’s prologue, and it immediately reorients the reader. Wilde loves his wife—either that, or he’s one of the world’s great pretenders. This is your starting point.

Letters between the Marquess of Queensbury and Lord Alfred Douglas. The father threatens to disown the son unless “your intimacy with this man Wilde [ceases].” Douglas replies by telegraph: “What a funny little man you are.”

Transcripts from the libel suit and criminal trial. Wilde’s repartee shines, but the flamboyance that made him the toast of England cannot save him. Even so, you can see why he might have thought so. He is a master of gloss and wit.

Letters between Wilde’s two adult sons. When the scandal broke, the two boys were whisked away to Europe with little understanding of their father’s circumstances. Although the move was intended to protect them, the adult Vyvyan explains, “You see, they got it all wrong, our grown-ups. It was the not knowing that was far worse.” Kirkus Reviews notes that “each of the Wildes’ two sons, so intensely beloved in early childhood by both parents, ends up psychologically damaged.”

These documents punctuate Bayard’s beautifully written scenes of a wife confronting her husband’s secret life and the mother and sons in exile. The novel includes profiles of each adult son in the World War I era. Bayard closes with a brief alternative history for his readers’ consideration, a sketch of what might have been. Some readers may see it as problematic. Others will long for it.

The novel doesn’t moralize.

Bayard doesn’t spend time condemning British society—readers can do this for themselves. He details Wilde’s recklessness, but doesn’t judge it. He allows Constance, Cyril, and Vyvyan to describe their own struggles with loss and betrayal. Kirkus Reviews suggests that in this novel, “Oscar’s sexual orientation is less important than his selfishness, pride, weakness, and capacity for abiding love.” My own view of Wilde is gentler—he appears to be more self-deluded than selfish. He floats in a cloud of magical thinking, assuming he can juggle his separate lives and keep everyone happy. Believing in his own invulnerability, Wilde seems confident that his charm and popularity will shield him from society’s wrath.

I don’t remember when I became enamored of Wilde’s writing. I read The Picture of Dorian Gray as a teenager—and what a superb story it is! In college, a friend had a part in The Importance of Being Earnest” and I attended rehearsals. I was enthralled by the play’s blend of sophistication and romance. Wilde’s dialogue is effervescent. And somewhere along the line, while I was admiring the writer, I learned what had happened to the man.

If you're familiar with Wilde’s tragedy, you’ll begin this novel with a sense of dread. Early on, when Wilde tells Constance that Douglas will be visiting, she has “only the faintest prickling of curiosity.” “Tell me if I’ve met this one,” she replies. She considers which room the guest will take and how much luggage he will bring. After some back-and-forth with her husband, she finally says, “I remember him now . . . His father is the Marquess of Queensbury.”

But knowing the history isn’t required, and this novel’s value extends far beyond the specific story it tells. The Wildes delves into the mysteries of complicated individuals and the enigmas of human longing. It explores the subtleties and shadows of imperfect beings and the gray areas of what we owe one another.

What are your thoughts on Oscar Wilde—the author and the man? If you’ve read The Wildes, please share your views. How would you judge Bayard’s alternative history at the end?

I love this novel so much! When I first heard about it, I pre-ordered it months before, devoured it in two days and wrote an Amazon rave. What a deep, rich idea to write this terrible history from the pov of the tragic wife and sons. One of my friends who is passionate about Wilde said he was shocked that he had seldom thought of what the whole sordid lying adultery thing did to Constance. Martha, I love what you said: "[Wilde] appears to be more self-deluded than selfish. He floats in a cloud of magical thinking, assuming he can juggle his separate lives and keep everyone happy." I think many married people who have affairs think like that but they don't take on the force of the late Victorian cruel court sentencing. A strong review of a strong book.

Ones again truth is stranger than fiction, and this review has its own touch of magic. Definitely adding to my must read list